© Commonwealth Ombudsman | 1300 362 072 | ombudsman.gov.au | phio.info@ombudsman.gov.au

Private Health Insurance Quarterly Bulletin 85

(1 October–31 December 2017)

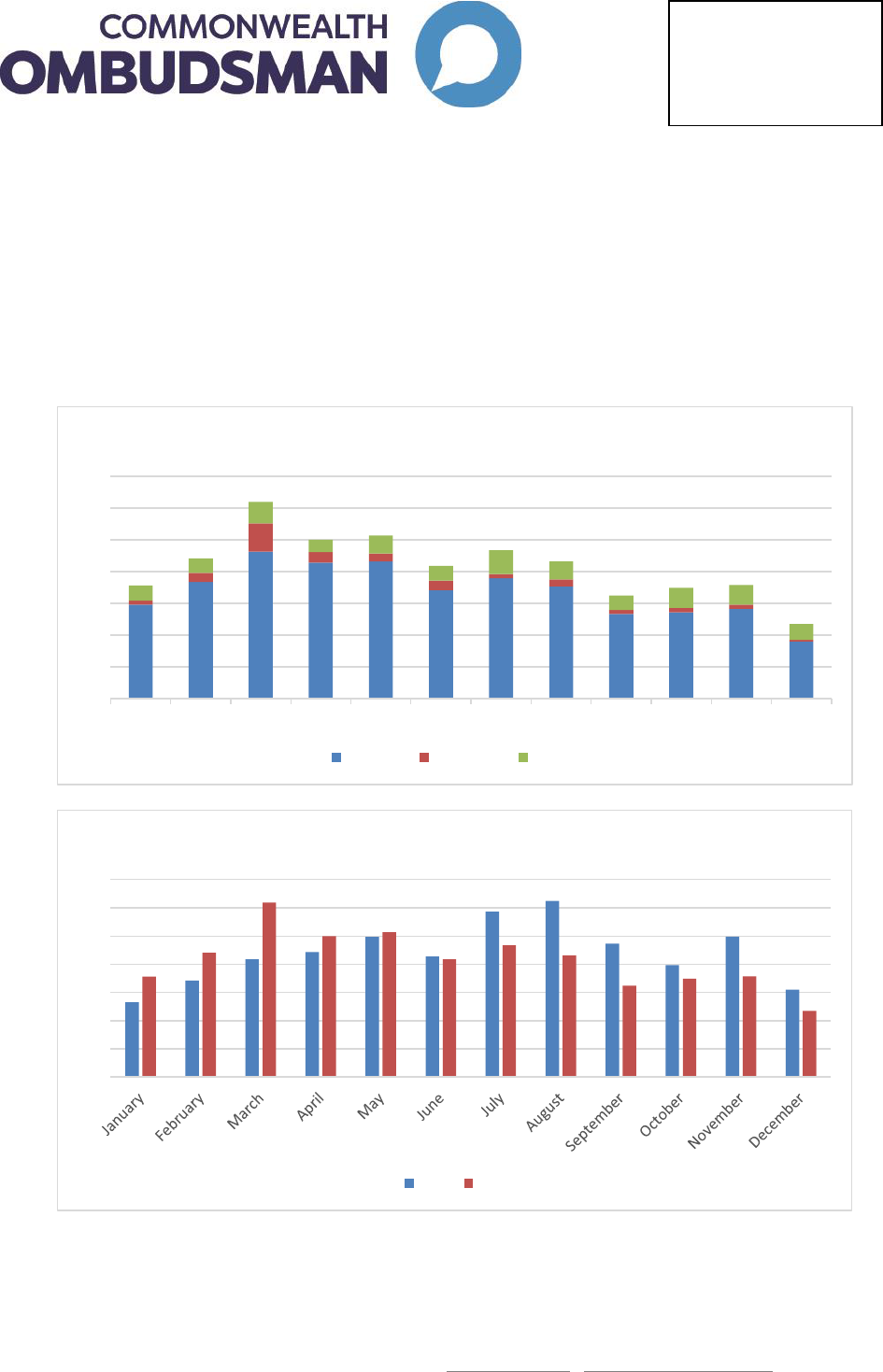

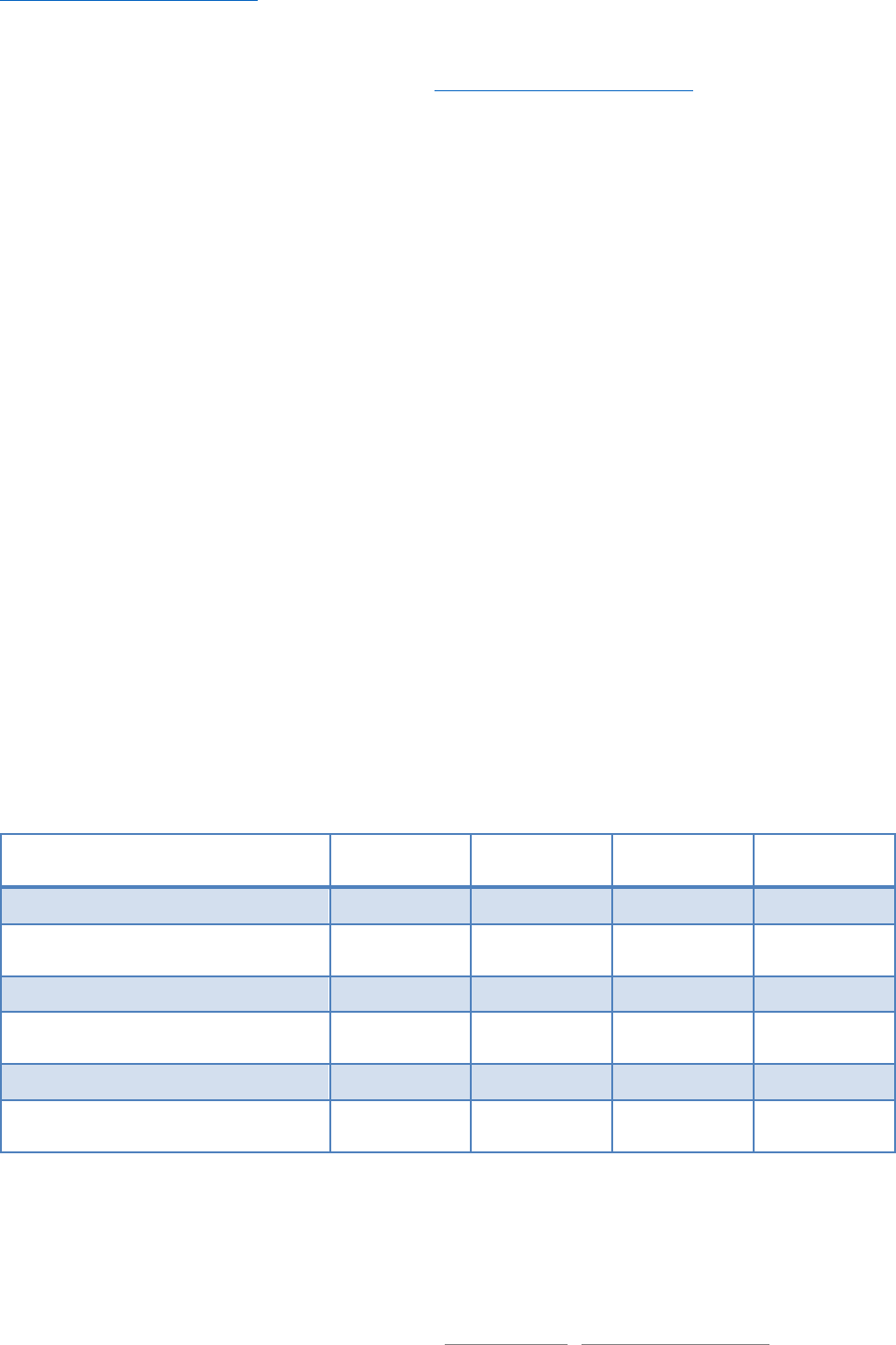

Complaint statistics this quarter

The Office of the Commonwealth Ombudsman (the Office) is pleased to report that private health insurance

complaints have returned to more average levels after a busy few quarters since mid-2016. Our Office

received 940 private health insurance complaints in this quarter. We received 1,204 complaints in the same

quarter last year, which represents a decline of 22 per cent from 2016 to 2017. In the previous quarter

ending September 2017, our Office received 1,222 complaints—representing a decline of 23 per cent.

0

100

200

300

400

500

600

700

Jan 17 Feb 17 Mar 17 Apr 17 May 17 Jun 17 Jul 17 Aug 17 Sep 17 Oct 17 Nov 17 Dec 17

Complaints by month

Problem Grievance Dispute

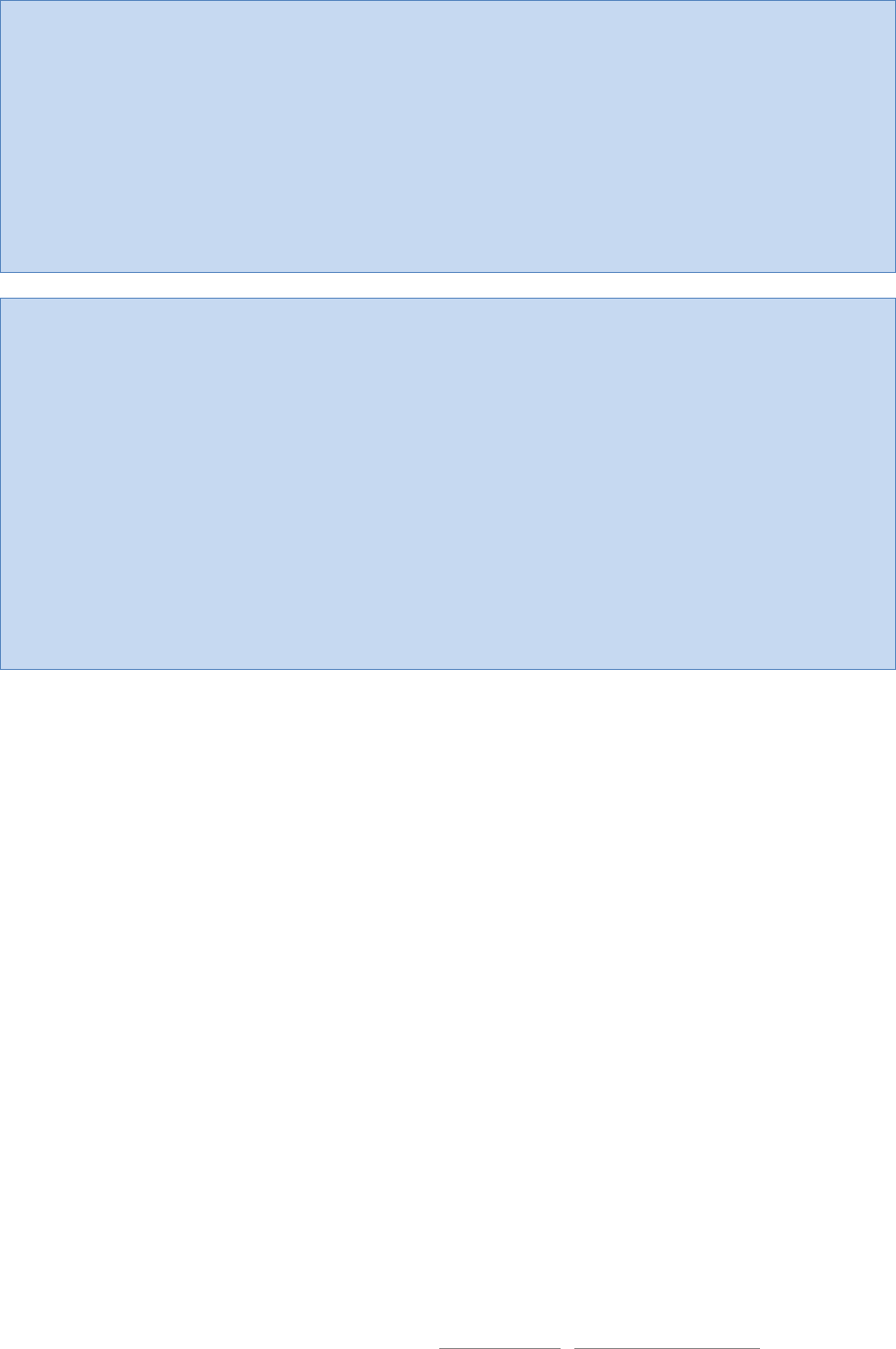

0

100

200

300

400

500

600

700

2016 compared to 2017

2016 2017

Issues in this bulletin

- Complaint statistics

- Ambulance bill complaints

- Lifetime Health Cover

- Top five complaint issues

© Commonwealth Ombudsman | 1300 362 072 | ombudsman.gov.au | phio.info@ombudsman.gov.au

Ambulance cover complaints

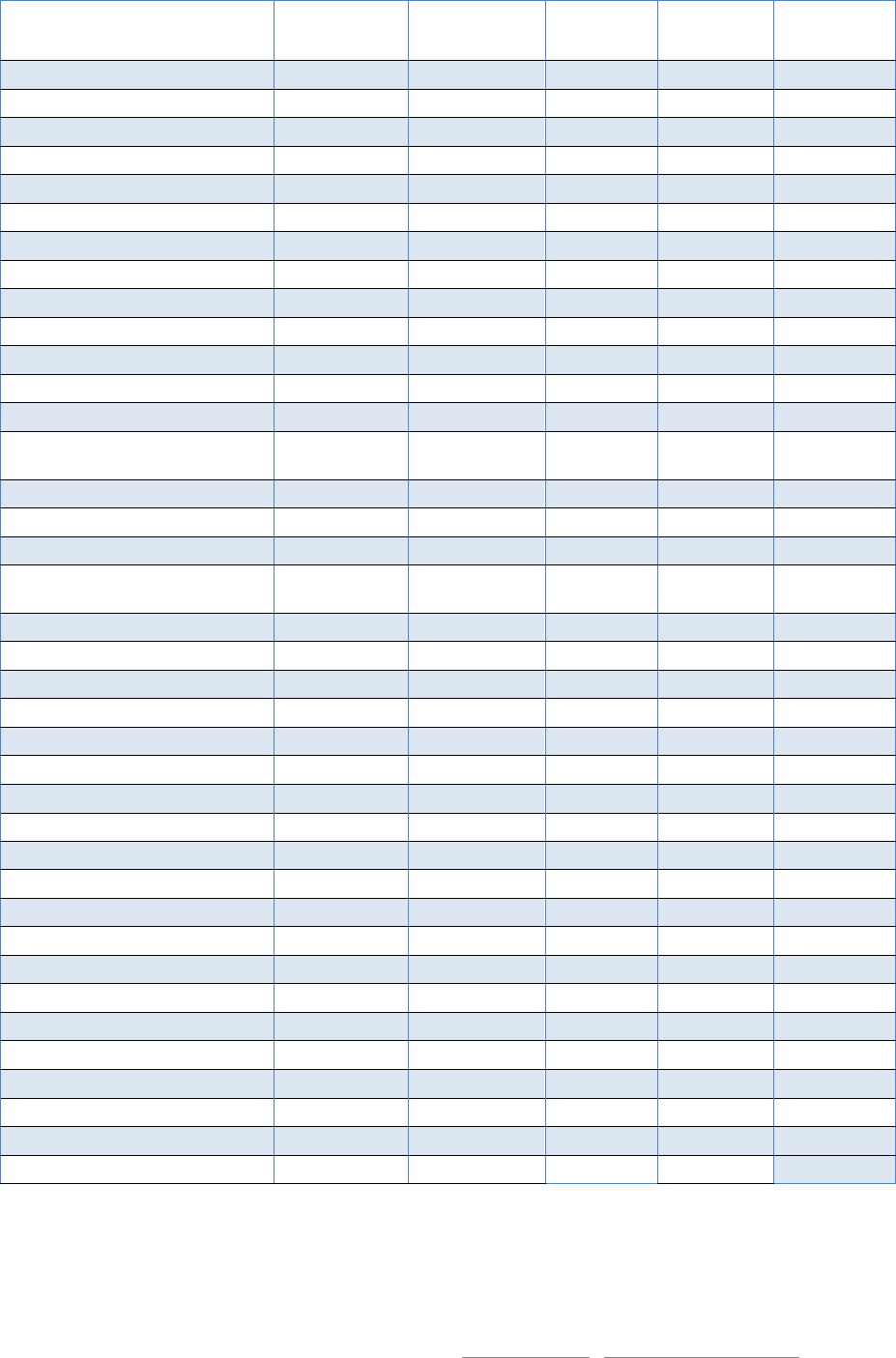

One area of complaints that has been increasing is ambulance cover complaints.

Ambulance costs in Australia are covered by a mix of government-regulated and private health insurance

arrangements. For a consumer seeking cover for ambulance costs, the Office recommends they carefully

consider the following questions, in addition to standard health insurance considerations:

Will the policy cover me when I'm travelling interstate?

Does the policy cover emergency situations only, or will it cover non-emergency as well? How

does the fund define an emergency?

What types of ambulance transport will this cover—for example, will it cover air ambulance? Will

it cover transport provided by state-approved private providers or other private providers?

Will the policy cover me for the ambulance 'call-out' fee if I need ambulance treatment but don't

require transportation?

Will I need to make any co-payments towards the ambulance fee?

It is perhaps not surprising that some health insurance consumers find it difficult to understand their health

insurance cover for ambulance given that the policy varies depending on where they are in Australia, what

‘code’ the ambulance service uses to categorise their service, who owns the ambulance and where they are

transported. It is understandable that some consumers feel that if they have a genuinely urgent need for

treatment and hold ambulance cover or a subscription they will be covered—unfortunately, there are some

instances where policy exclusions mean they are not covered.

Case study one

Willis, a resident of New South Wales, was on holiday in the Northern Territory visiting Alice Springs and

the surrounding area. On a very hot day, while near Alice Springs, he suffered dehydration and sunstroke.

Due to the limited medical facilities in Alice Springs and the vast distance to public hospitals, Willis was

transported by the Royal Flying Doctor Service’s air ambulance to a public hospital in South Australia.

His health insurer received his claim for the ambulance transport but refused to pay telling him that he

had used an ‘unrecognised provider’. Willis’ policy was one that covered recognised ambulance services,

including air ambulance services, throughout Australia. However it seemed that his insurer did not

recognise any air ambulance providers in the Northern Territory, and only recognised providers of road-

based ambulance transport in the vicinity of the two metropolitan cities.

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

2007-08 2008-09 2009-10 2010-11 2011-12 2012-13 2013-14 2014-15 2015-16 2016-17

Ambulance cover complaints by year

© Commonwealth Ombudsman | 1300 362 072 | ombudsman.gov.au | phio.info@ombudsman.gov.au

Willis contacted our Office to complain because he felt he had been given no choice of ambulance

provider at the time he sought medical help. He also felt that he had taken a policy that included

ambulance cover throughout Australia, but it didn’t cover most of the Northern Territory because the

insurer did not recognise the only air ambulance provider in that state.

Our investigation showed that Willis’ policy did indeed offer to cover him for ambulance throughout

Australia. It was therefore reasonable for a policyholder to expect that the insurer had ensured that it had

sufficient recognised ambulance providers throughout the country. Based on this view, the insurer

decided to pay Willis’s ambulance bill and to review its ambulance policy.

Case study two

Zelda broke her leg and ankle when she was out bushwalking in regional Victoria. On Monday, she was

taken to the nearest public hospital by ambulance. She was then transported to a private hospital and

received treatment within the hour. A week later, on Sunday, Zelda experienced post-operative

complications and called the ambulance to be transported to the nearest hospital.

Zelda’s policy was limited to two ambulance claims per year. Initially, the insurer refused to pay the most

recent service because they considered Zelda’s first service on Monday to be two claims—the trip to the

public hospital and then the transport to the private hospital.

In the Office’s view, this wasn’t reasonable as from Zelda’s perspective she had only been treated after

being transported to the second hospital and therefore this was one claim. After reviewing the case, the

health fund agreed to treat the first two transfers as one claim and also paid for the Sunday claim.

Hospital to hospital ambulance issues

Many of the ambulance bill complaints that our Office investigates seem to occur where there is some

ambiguity about who is responsible for paying an ambulance transport bill, or whether it should be issued in

the first place. For example, if a small regional hospital admits a patient who arrives by emergency

ambulance only to transfer them to a larger metropolitan hospital, then an ambulance account is usually

paid for by the ‘losing’ hospital that couldn’t treat the patient.

If, however, the losing hospital doesn’t formally admit the patient and instead treats them as an outpatient,

they can avoid paying the ambulance account because they no longer consider it a ‘hospital to hospital’

transfer. If a hospital chooses not to admit a patient and instead books a second ambulance to send them to

another hospital, the ambulance bill becomes the responsibility of the patient to pay.

The problem for health insurance consumers is that all ambulance policies exclude hospital to hospital

transfers and most won’t pay for non-emergency transport either. In some instances, consumers are

incurring costs of up to $5,000 when they are treated on an outpatient basis by a local hospital which then

transfers them to another hospital.

Issuing a patient with an ambulance bill is a concerning practice for a number of reasons:

Patients who make the effort to pay for health insurance ambulance cover consider it is unfair to be

charged due to gaps existing in the system. Although there are not many instances of this type of

failure in the system occurring, for the unlucky few, the out-of-pocket costs can be considerable.

© Commonwealth Ombudsman | 1300 362 072 | ombudsman.gov.au | phio.info@ombudsman.gov.au

Treatment provided during the process of transporting a patient to one hospital and then forwarding

them to another hospital is likely to be seen as a ‘hospital to hospital’ admission by the patient

because they are physically present in the hospital. The distinction between outpatient and inpatient

treatment is, from their perspective, only an administrative detail.

It has long been the practice that hospitals that are unable to treat a patient that is brought to them

by ambulance look after the booking and costs of forwarding that patient to another hospital, so

these costs usually come as a surprise to patients.

Many of these complaints are resolved by pointing out that the system should not allow hospital bills to

become the complainant’s responsibility. Fully insured patients and anomalous accounts can be shared

between hospitals and health insurers on a case-by-case basis. Fortunately the number of patients being

billed for ambulance services in this manner is low.

The private health insurance system is not currently designed to pay for hospital to hospital transfers. Our

Office will continue monitoring these complaints and discuss our concerns with the public hospitals,

ambulance providers and health insurers involved.

Lifetime Health Cover

The Lifetime Health Cover (LHC) rules determine how much a person pays for Australian hospital insurance.

A person’s LHC ‘loading’ is the extra amount they pay on top of the base premium if they have missed their

window to purchase hospital insurance at the base rates. The current rules are contained in the Private

Health Insurance Act 2007 (Cth).

Due to the complexity of the rules, LHC is one of the most common topics that consumers raise when they

contact our Office. Health insurers also contact our Office from time to time to seek clarification.

Health insurer staff and health insurer websites should incorporate appropriate LHC questions into the join

or transfer process, so that a person’s LHC can be established as quickly and accurately as possible. Some

important questions to ask new members include:

Has the person held hospital insurance in Australia before and if so, when?

Are they a new migrant?

o If so, when did they enrol for their first interim or permanent Medicare card? (Note that a

person with reciprocal Medicare is not liable to pay LHC loading.)

Has the person been overseas for any extended periods and if so, when?

If necessary, ask the person to supply clearance certificates from their previous insurers and an

International Movement record from the Department of Home Affairs, to establish their loading.

Below we outline three LHC scenarios which are frequently raised by consumers and insurers contacting our

Office for assistance:

New migrant to Australia, overseas on their base day on or after 1 July 2010

Generally, a person must hold private hospital insurance by the later of the 1 July following their 31

st

birthday or 1 July 2000 to avoid incurring LHC loading. However, some exemptions do exist for certain

groups. New migrants who are aged over 31 have until the first anniversary of their first Medicare

enrolment to take up private hospital insurance without loading. Furthermore, if they enrolled in Medicare

from 1 July 2009 onwards, then they are eligible for a further extension if they are overseas on their

Medicare anniversary day.

© Commonwealth Ombudsman | 1300 362 072 | ombudsman.gov.au | phio.info@ombudsman.gov.au

Yuna came to Australia on a working visa and later applied for permanent residency. On receiving her

bridging visa in 2015, she became eligible for Medicare and enrolled for an interim Medicare card in June

2015. She was then aged 35.

New migrants usually have 1 year from their first Medicare enrolment (at either an interim or permanent

level) to take up private hospital cover without incurring LHC loading. So this would place Yuna’s usual LHC

‘base day’ at June 2016. However, Yuna was actually living overseas for the period from April 2016

through to August 2017. She was therefore eligible for an extension as she was overseas on her base day.

The LHC rules state that if a new migrant is overseas on their base day, and their base day falls on or after

1 July 2010, then a further extension applies. They have one year from their first permanent return to

Australia to take up insurance without incurring a loading. Their ‘first permanent return’ is their first visit

back to Australia of 90 days or more.

Yuna returned in August 2017, so she has until August 2018 to take up insurance without loading. She will

need to supply her insurer with a Medicare letter confirming her enrolment date to establish her original

LHC base day and an International Movement record from the Department of Home Affairs, to establish

that she was overseas on the base day and first returned in August 2017.

If Yuna misses the August 2018 extension, even if she is overseas again at that date, no further

exemptions apply. A full loading based on her age at the time of joining will apply if she joins after August

2018.

The 10 year rule and ‘days of absence’

Under the LHC rules, a person’s loading is removed if they complete 10 years of hospital cover. They can

break up the 10 years using the ‘permitted periods without hospital cover’ as outlined in section 34–20 of

the Act. However, if the person subsequently drops their hospital insurance again and then picks it up at a

later time, having used up all their permitted periods, then they will incur their previous loading back again

as well as any further loading that has since accrued.

Ethan commenced hospital insurance at age 35 in 2002, incurring a 10 per cent loading. He completed 10

years of hospital cover in 2012, and his loading was subsequently reduced to zero. He continued his cover

for two more years. At age 47 in 2014, he cancelled his hospital insurance.

On cancelling his insurance, Ethan had access to the usual permitted periods without hospital cover which

are: suspension, going overseas for at least 12 months, and 1,094 ‘days of absence’ (three years less one

day). He did not suspend his insurance or go overseas for an extended period, so his time without

insurance was deducted from his 1,094 days of absence.

In 2017, he used up his full 1,094 days of absence.

In 2018, he re-joined private hospital insurance. He had used up his 1,094 days of absence, so two per

cent loading had accrued for the one further year he was without cover after the days of absence expired.

In addition to this, he re-gained his previous loading of 10 per cent.

Therefore his total loading on re-joining in 2018 was 12 per cent. Ethan needs to complete a further 10

years of continuous hospital insurance to reduce his loading to zero again.

It’s important to note that he has no further days of absence. If Ethan has even a small break of one day in

future (e.g. switching between insurers), this will potentially cause him to have to re-start his 10 years

again. The only time he can be without insurance and still have continuity of the 10 years will be if he

suspends his insurance or goes overseas for a period of at least 12 months.

© Commonwealth Ombudsman | 1300 362 072 | ombudsman.gov.au | phio.info@ombudsman.gov.au

Australian, over 31, and overseas on 1 July 2000

There is one specific LHC exemption for Australians who were aged over 31 and were living overseas on

1 July 2000 which is different from almost all other exemptions. These individuals are able to return to

Australia and access the 1,094 days of absence, even though they have not previously held private hospital

cover.

Anaya departed Australia in 1998 to live overseas. She was aged 40 when she departed. Over the next

twelve years, she returned to Australia from time to time, mostly for short visits but including one long

visit of 12 months in 2007–08.

In 2010, she returned to Australia permanently, she was then aged 52. In 2017, at age 59, she purchased

private hospital cover.

Initially her insurer applied a LHC loading of 58 per cent, based on her age in 2017. However, there is a

specific LHC clause which provides a different outcome for people who were Australians or permanent

residents on 1 July 2000 who were also aged over 31 and overseas on that date. People who meet this

specific criteria are ‘taken to have had hospital cover’ on their LHC base day and therefore have access to

all the usual permitted periods without hospital cover.

This means they are considered to have zero loading at 1 July 2000. Any subsequent periods of time spent

overseas for 12 months or more do not count towards LHC loading, and any returns to Australia are

deducted from the 1,094 days of absence. Once the 1,094 days have been used up, the person

accumulates two per cent loading for each further year without hospital cover.

For Anaya, this means she had zero loading on her base day of 1 July 2000. It remained at zero for the

period from 1 July 2000 to her return in 2007 as she was overseas for a period of 12 months or more,

which is a permitted period without hospital cover.

In 2007 she returned for a period of 12 months. Her loading remained at zero, but this period is deducted

from her 1,094 days (three years less one day) of absence.

She went back overseas and her loading stayed at zero as the period was 12 months or more.

She returned in 2010. From 2010 onwards she began to use up the remaining two years of her 1,094 days

of absence, with the days of absence expiring in 2012. From 2012 onwards she began to accumulate two

per cent loading for each further year without hospital insurance.

By the time she joined in 2017, she had accumulated 12 per cent LHC loading.

Anaya then produced her International Movement record, showing her entries and exits from Australia,

and asked the insurer to review her LHC loading. Her insurer corrected the loading to 12 per cent and

refunded the excess she had paid in premiums. If Anaya completes 10 continuous years of private hospital

cover, her loading will be reduced to zero.

Further Resources:

The Office’s website privatehealth.gov.au includes the following resources:

LHC Calculators

Information on LHC

LHC brochure available in several community languages.

In the first instance, consumers should speak to their insurer for more advice. If they require further

assistance, they can contact our Office directly for more information on our enquiries line 1300 737 299 or at

© Commonwealth Ombudsman | 1300 362 072 | ombudsman.gov.au | phio.info@ombudsman.gov.au

phio.info@ombudsman.gov.au. If a consumer wishes to lodge a complaint against their insurer, they can call

our complaints line 1300 362 072 or complete the online complaints form at ombudsman.gov.au.

Insurer staff seeking further advice should first contact the compliance or training staff in their organisation.

For complex queries, our Office can be contacted at phio.in[email protected]ov.au.

Top five consumer complaint issues this quarter

1. Hospital exclusions and restrictions: 105 complaints—usually caused when complainants find they

are not covered for a service or treatment that they had assumed was included in their cover.

2. General treatment (extras/ancillary): 77 complaints—these complaints usually concern disputes

over the amount payable under ‘extras’ policies, such as dental, optical, physiotherapy, and

pharmaceuticals, or the insurer’s rules for benefit payments (such as certain minimum claim

criteria).

3. Membership cancellation: 76 complaints—complaints caused by problems and delays associated

with processing requests to cancel memberships and handling payments or refunds. It’s important

to note that in most cases these membership cancellations are caused by consumers transferring

from one insurer to another and not the result of people leaving health insurance altogether.

4. Pre-existing conditions waiting period: 75 complaints—these complaints are usually caused by the

health insurer or the insurer’s medical practitioner failing to clearly state which signs and symptoms

were relied upon in assessing a claim and the complainant misunderstanding how a pre-existing

condition is defined.

5. Verbal advice: 64 complaints—most verbal advice complaints concern consumers misunderstanding

their benefits during telephone calls and retail branch visits with their insurer, particularly where

records are not adequately maintained. In many cases our case officers will access the recording of

advice provided to a consumer and provide an independent assessment of the quality of the

information provided.

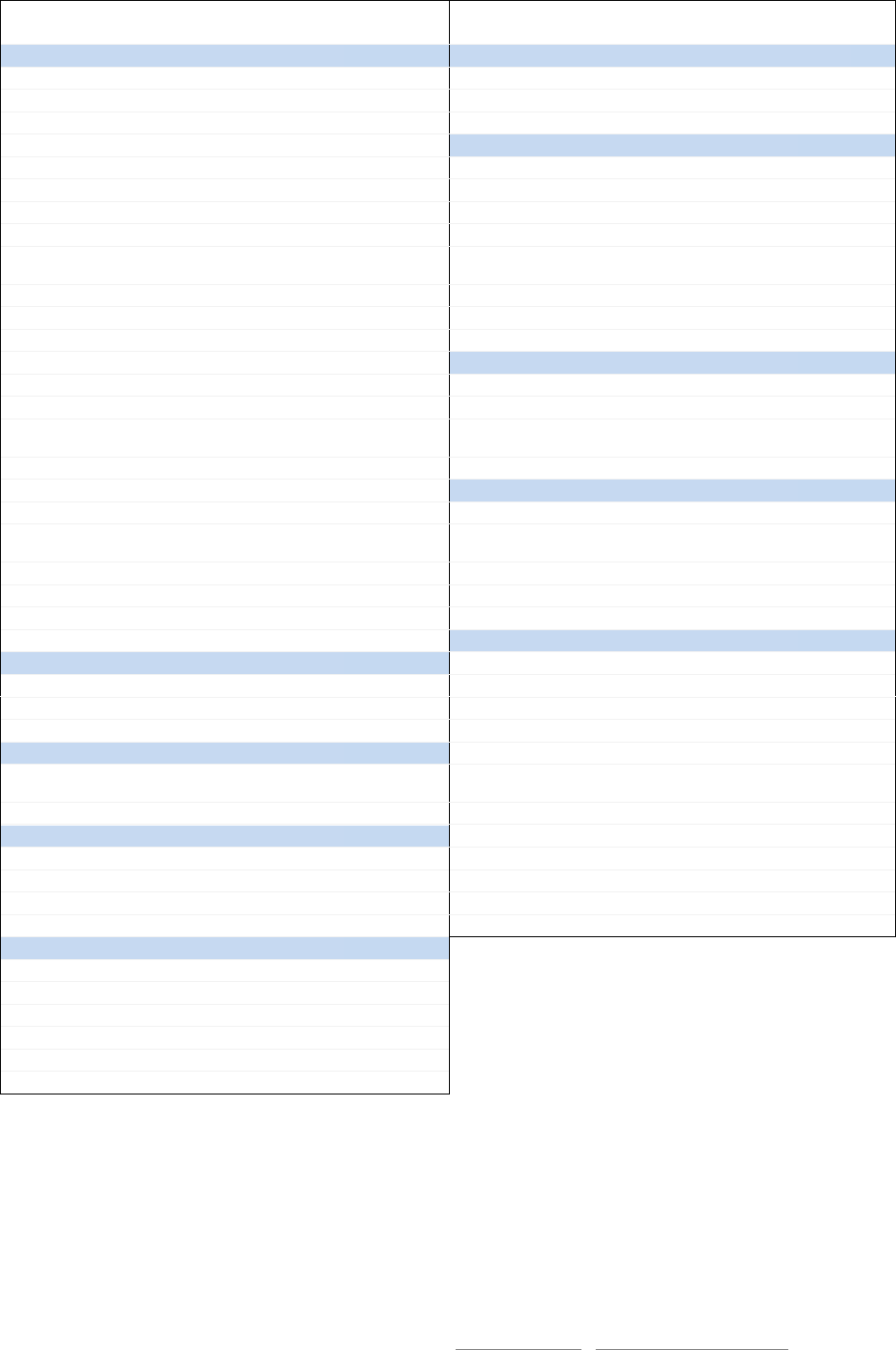

Complaints by provider or organisation type

Provider or organisation type

Mar 2017

QTR

Jun 2017 QTR

Sep 2017 QTR

Dec 2017 QTR

Health insurers

1,245

1,237

1,020

780

Overseas visitor & overseas student

health Insurers

108

114

141

114

Brokers and comparison services

19

25

26

17

Doctors, dentists, other medical

providers

6

13

4

3

Hospitals and area health services

15

17

13

15

Other (e.g. legislation, ambulance

services, industry peak bodies, etc.)

19

25

18

11

© Commonwealth Ombudsman | 1300 362 072 | ombudsman.gov.au | phio.info@ombudsman.gov.au

Subscribe for updates

To be added to our distribution list for private health insurance news and publications, sign up using our

online form or email phio.info@ombudsman.gov.au.

You can also follow us on Facebook for updates: facebook.com/commonwealthombudsman/

For general private health insurance information and to compare health insurance policies, visit

privatehealth.gov.au

© Commonwealth Ombudsman | 1300 362 072 | ombudsman.gov.au | phio.info@ombudsman.gov.au

Complaints by health insurer market share

1 October to 31 December 2017

Name of Insurer

Complaints(1)

Percentage of

complaints

Disputes(2)

Percentage

of disputes

Market

share(3)

ACA Health Benefits

0

0.0%

0

0.0%

0.1%

Australian Unity

49

6.3%

8

6.8%

3.0%

BUPA

222

28.5%

48

41.0%

27.0%

CBHS Corporate Health

0

0.0%

0

0.0%

<0.1%

CBHS

12

1.5%

1

0.9%

1.5%

CDH (Cessnock District Health)

0

0.0%

0

0.0%

<0.1%

CUA Health

7

0.9%

1

0.9%

0.6%

Defence Health

4

0.5%

0

0.0%

2.0%

Doctors' Health Fund

2

0.3%

0

0.0%

0.3%

Emergency Services Health

0

0.0%

0

0.0%

<0.1%

GMHBA

23

2.9%

2

1.7%

2.3%

Grand United Corporate Health

5

0.6%

0

0.0%

0.4%

HBF Health & GMF/Healthguard

38

4.9%

5

4.3%

8.0%

HCF (Hospitals Contribution

Fund)

111

14.2%

20

17.1%

10.4%

Health.com.au

11

1.4%

5

4.3%

0.6%

Health Care Insurance

1

0.1%

0

0.0%

0.1%

Health-Partners

2

0.3%

0

0.0%

0.6%

HIF (Health Insurance Fund of

Aus.)

7

0.9%

1

0.9%

0.9%

Latrobe Health

3

0.4%

0

0.0%

0.7%

Medibank Private & AHM

183

23.5%

12

10.3%

26.9%

Mildura District Hospital Fund

0

0.0%

0

0.0%

0.2%

MO Health Pty Ltd

0

0.0%

0

0.0%

<0.1%

National Health Benefits Aust.

0

0.0%

0

0.0%

0.1%

Navy Health

1

0.1%

0

0.0%

0.3%

NIB Health

62

7.9%

7

6.0%

8.3%

Nurses and Midwives Pty Ltd

1

0.1%

0

0.0%

<0.1%

Peoplecare

7

0.9%

1

0.9%

0.5%

Phoenix Health Fund

1

0.1%

1

0.9%

0.1%

Police Health

0

0.0%

0

0.0%

0.3%

QLD Country Health Fund

1

0.1%

0

0.0%

0.4%

Railway & Transport Health

7

0.9%

2

1.7%

0.4%

Reserve Bank Health

0

0.0%

0

0.0%

<0.1%

St Lukes Health

0

0.0%

0

0.0%

0.5%

Teachers Federation Health

16

2.1%

2

1.7%

2.3%

Teachers Union Health

2

0.3%

0

0.0%

0.6%

Transport Health

1

0.1%

0

0.0%

0.1%

Westfund

1

0.1%

1

0.9%

0.7%

Total for Health Insurers

780

100%

117

100%

100%

1) Total number of Complaints (Problems, Grievances & Disputes) regarding Australian registered health insurers. This table excludes

complaints regarding OVHC and OSHC insurers, and other bodies.

2) Disputes required the intervention of the Ombudsman and the health insurer.

3) Source: Australian Prudential Regulation Authority, Market Share, All Policies, 30 June 2017.

© Commonwealth Ombudsman | 1300 362 072 | ombudsman.gov.au | phio.info@ombudsman.gov.au

Issues and sub-issues: complaints received in previous four quarters

ISSUE

Mar

17

Jun

17

Sep

17

Dec

17

ISSUE

Mar

17

Jun

17

Sep

17

Dec

17

Sub-issue

Sub-issue

BENEFIT

INFORMED FINANCIAL CONSENT

Accident and emergency

10

10

20

16

Doctors

7

7

1

0

Accrued benefits

2

3

1

2

Hospitals

10

17

9

12

Ambulance

17

21

16

21

Other

0

3

2

1

Amount

51

54

32

17

MEMBERSHIP

Delay in payment

54

70

43

28

Adult dependents

5

9

7

1

Excess

22

16

17

21

Arrears

31

14

23

14

Gap - Hospital

22

23

13

25

Authority over membership

3

3

3

8

Gap - Medical

33

29

25

33

Cancellation

97

111

97

76

General treatment

(extras/ancillary)

52

36

59

77

Clearance certificates

41

57

50

18

High cost drugs

4

2

1

3

Continuity

47

44

31

18

Hospital exclusion/restriction

73

90

120

105

Rate and benefit protection

4

9

1

0

Insurer rule

38

30

27

24

Suspension

23

22

26

15

Limit reached

6

4

14

3

SERVICE

New baby

6

6

8

3

Customer service advice

32

53

41

19

Non-health insurance

5

1

0

2

General service issues

81

65

55

42

Non-health insurance - overseas

benefits

0

0

0

0

Premium payment problems

127

163

57

36

Non-recognised other practitioner

6

9

4

2

Service delays

60

45

21

18

Non-recognised podiatry

4

5

1

1

WAITING PERIOD

Other compensation

3

6

7

3

Benefit limitation period

0

0

1

0

Out of pocket not elsewhere

covered

9

5

5

6

General

6

6

10

9

Out of time

5

3

4

10

Obstetric

7

11

9

9

Preferred provider schemes

19

15

11

9

Other

4

6

6

3

Prostheses

1

5

0

2

Pre-existing conditions

59

88

93

75

Workers compensation

1

2

1

0

OTHER

CONTRACT

Access

1

0

0

0

Hospitals

10

4

8

2

Acute care certificates

1

3

1

2

Preferred provider schemes

2

8

6

5

Community rating

0

0

1

0

Second tier default benefit

1

1

0

0

Complaint not elsewhere covered

24

24

14

10

COST

Confidentiality and privacy

4

2

4

2

Dual charging

4

0

0

0

Demutualisation/sale of health

insurers

1

0

0

1

Rate increase

95

32

8

4

Discrimination

0

0

0

0

INCENTIVES

Medibank sale

1

0

1

0

Lifetime Health Cover

46

63

55

27

Non-English speaking background

0

0

0

0

Medicare Levy Surcharge

1

2

4

2

Non-Medicare patient

2

3

3

0

Rebate

9

11

4

3

Private patient election

3

2

1

0

Rebate tiers and surcharge changes

2

0

0

1

Rule change

33

14

6

0

INFORMATION

Brochures and websites

16

15

12

6

Lack of notification

11

15

15

19

Oral advice

80

87

91

64

Radio and television

1

0

0

0

Standard Information Statement

1

1

3

0

Written advice

21

8

9

6