Substance Abuse and Mental Health

Services Administration

Harm Reduction

Framework

Public Domain Notice

All material appearing in this publication is in the public domain and may be reproduced or

copied without permission from SAMHSA. Citation of the source is appreciated. However,

this publication may not be reproduced or distributed for a fee without the specific, written

authorization of the Office of Communications, SAMHSA, HHS.

Electronic Access and Copies

Products may be downloaded at https://www.samhsa.gov/find-help/harm-reduction/

framework

Recommended Citation

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: Harm Reduction Framework.

Center for Substance Abuse Prevention, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services

Administration, 2023.

Originating Office

Center for Substance Abuse Prevention, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services

Administration, 5600 Fishers Lane, Rockville, MD 20857.

Nondiscrimination Notice

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) complies with

applicable Federal civil rights laws and does not discriminate on the basis of race, color,

national origin, age, disability, religion, or sex (including pregnancy, sexual orientation,

and gender identity). SAMHSA does not exclude people or treat them differently because

of race, color, national origin, age, disability, religion, or sex (including pregnancy, sexual

orientation, and gender identity).

Harm Reducon Framework

3

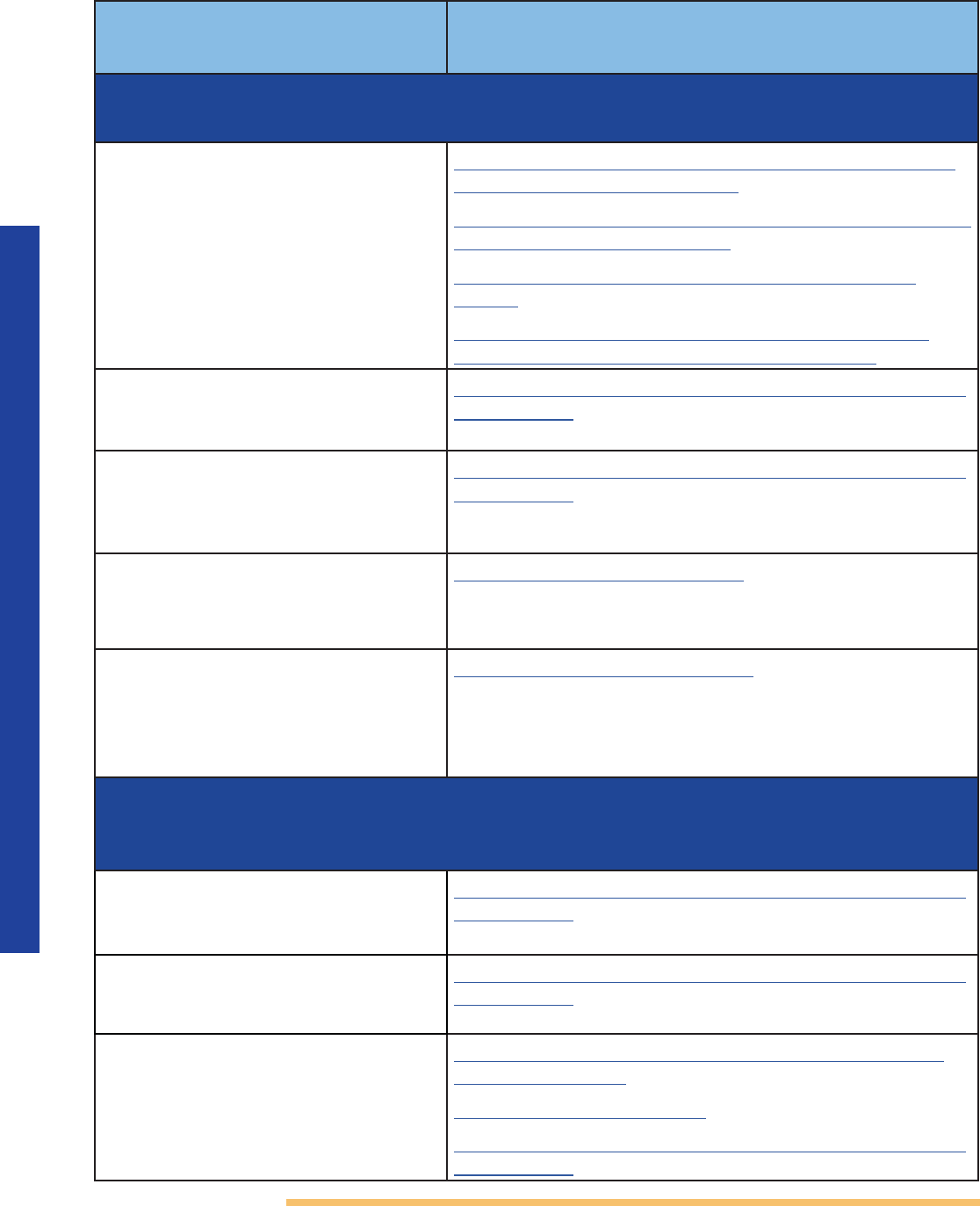

Contents

Harm Reduction Framework for People Who Use Drugs (PWUD) ...................................................... 4

Brief History and Background of Harm Reduction

........................................................................................5

Addressing Health Inequities

......................................................................................................................................... 6

Framework Overview

.......................................................................................................................................................... 6

• Framing Harm Reduction.................................................................................................................................7

• Pillars of Harm Reduction .................................................................................................................................8

• Table 1. Six Pillars of Harm Reduction .......................................................................................................8

• Supporting Principles ........................................................................................................................................10

• Table 2. Principles of Harm Reduction ................................................................................................... 10

• Core Practice Areas.................................................................................................................................................. 12

• Table 3. Core Practice Areas ........................................................................................................................... 12

• Community-Based Harm Reduction Programs (CHRPs) ......................................................... 17

Conclusion

............................................................................................................................................................................ 17

References

............................................................................................................................................................................18

Harm Reduction Steering Committee Members

......................................................................................... 25

Harm Reducon Framework

4

Harm Reduction Framework for People Who

Use Drugs (PWUD)

The Biden-Harris Administration has identified harm reduction as a federal drug policy

priority. The White House Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP), in the 2022

National Drug Control Strategy, notes that harm reduction is a public health approach

designed to advance policies and programs in collaboration with people who use drugs

(PWUD) and is supported by decades of evidence. Harm reduction strategies are shown to

substantially reduce HIV and hepatitis C infection among people who inject drugs, reduce

overdose risk, enhance health and safety, and increase by five-fold the likelihood of a person

who injects drugs to initiate substance use disorder treatment.

1, 2, 3

In line with this, harm

reduction is one of the four strategic priorities of the U.S. Department of Health and Human

Services (HHS) Overdose Prevention Strategy developed to address the overdose public

health emergency.

4

In December 2021, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration

(SAMHSA) convened the first-ever federal Harm Reduction Summit, in partnership with

the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and ONDCP. The Summit brought

together more than 100 experts representing prevention, treatment, recovery, and harm

reduction perspectives. Most importantly, Summit attendees included people with lived

experience with substance use to help inform SAMHSA’s policies, programs, and practices

as they relate to harm reduction. Additional partners included community members,

advocates, harm reductionists, providers, funders, and others who are affected by these

issues.

SAMHSA’s Harm Reduction Framework is one outcome of the Summit. This Framework is

historic, as the first document to comprehensively outline harm reduction and discuss its

role throughout HHS.

The Framework was developed and written in partnership with the Harm Reduction

Steering Committee, composed of harm reduction leaders in the field from across the

country. This group represents a broad array of backgrounds and experience, with most

having lived experience of drug use. The Steering Committee synthesized findings from the

Summit ― including a definition of harm reduction, pillars and principles supporting that

definition, and core practices that SAMHSA can support. The Framework is adapted from

the Committee’s final report.

This Framework will inform SAMHSA’s harm reduction activities moving forward, as well

as related policies, programs, and practices. SAMHSA’s aim is to integrate harm reduction

activities and approaches across its organizational Centers and initiatives, and to do so in

a manner that draws on evidence-based practice and principles ― while also maintaining

sustained dialogue with harm reductionists and people who use drugs (PWUD). The

Framework will also inform SAMHSA’s thinking about opportunities to work with other

federal, state, tribal, and local partners toward advancing harm reduction approaches,

services, and programs.

SAMHSA defines harm reduction as a practical and transformative approach that

incorporates community-driven public health strategies — including prevention,

risk reduction, and health promotion — to empower PWUD and their families

with the choice to live healthier, self-directed, and purpose-filled lives. Harm

reduction centers the lived and living experience of PWUD, especially those in

underserved communities, in these strategies and the practices that flow from them.

Harm Reducon Framework

5

Brief History and Background of Harm

Reduction

Harm reduction has a long history in the United States. The field itself and harm reduction

practice emerged decades ago, as direct community action and mutual aid in response

to effects of the “War on Drugs,” an early and incomplete scientific understanding of

substance use and substance use disorders, and government inaction to swiftly respond to

the growing HIV/AIDS epidemic.

5

In 1982, CDC published findings that the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) is

transmissible through the intravenous use of drugs.

6

By 1983, PWUD began the

distribution of sterile syringes to limit the transmission of HIV/AIDS.

7

After the 1988

restriction on federal funding for the purchase of syringes for needle and syringe

exchange programs, PWUD and allies who operated syringe services programs

(SSPs) across the country began to organize their work.

8

In 1992, the first Harm

Reduction Working Group meeting in the United States was held in San Francisco to

create a unified definition of harm reduction. A major outcome of the group was the

establishment of the National Harm Reduction Coalition.

9

Since the first Harm Reduction Working Group meeting in 1992, harm reduction has

grown in scope and in practice. PWUD have innovated and sustained the movement

despite criminalization of many harm reduction interventions and lack of financial and

social support.

An important example is the advent of community naloxone distribution, which began

in 1996.

10

From 1996 through June 2014, 136 organizations reported distributing naloxone

to 152,283 laypersons. Of the 109 organizations who collect reversal data, 26,463 overdose

reversals were reported.

11

Although the number of organizations distributing naloxone

has doubled and since 2013 has included organizations other than SSPs, in 2014, SSPs

still accounted for 80 percent of the distribution effort to PWUD, as well as 80 percent of

overdose reversals.

12

In 2019, SSPs distributed 702,232 doses of naloxone to 230,506 people in communities

across the country.

13

Studies have shown that communities may experience up to a 46

percent reduction in opioid overdose mortality when more than 100 people who are likely

to observe or experience an overdose per 100,000 population are enrolled into an Overdose

Education and Naloxone Distribution (OEND) program.

14

In addition, SSPs are associated

with an estimated 50 percent reduction in HIV and hepatitis C incidence.

15,16

When

combined with medications that treat opioid use disorder (also known as medications for

opioid use disorder or MOUD), hepatitis C virus and HIV transmission is reduced by more

than two-thirds.

17

The last few decades have solidified the evidence-based practices and

individuals have become specialized subject matter experts in the field of harm reduction.

Harm Reducon Framework

6

Addressing Health Inequities

In the spirit of Executive Order 13985,

18

SAMHSA is in the process of reviewing its policies to

examine the intended and unintended impacts of its programs, policies, and procedures;

incorporating racial justice and health equity into its policy goals; and advancing equitable

support for Black, Latino, American Indian and Alaskan Native persons, Asian Americans,

Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders, and other persons of color; members of religious

minorities; lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, intersex (LGBTQI+) persons; persons

with disabilities; persons who live in rural areas; and persons otherwise adversely impacted

by persistent poverty or inequality. This is proactively undertaken to address past and

present inequities.

18

Integrating harm reduction principles and approaches throughout the

agency is one strategy for advancing that commitment.

Deficient social determinants of health and structural inequalities contribute to and

exacerbate substance use, substance use disorder, and mental illness, and can and do

have a profound impact on some populations. Most notably, persons who have a history of

familial, community or racial trauma may be particularly in need of compassionate services

to support their pathways to improved health outcomes. Community practitioners and

behavioral health providers must be culturally responsive and attentive to health equity

to effectively improve individual and population level health. For this to be accomplished,

community trust and buy-in must be earned, and that begins with truth and reconciliation

of a community’s shared traumatic history and the structural racism that perpetuates

inequities. On this foundation, trust and meaningful relationships can develop.

19

“Formally acknowledging a community’s shared

traumatic history is a fundamental step in preparing for

and planning community engagement (CE) efforts that

address health inequities.”

19

This work is undertaken in partnership with SAMHSA’s Office of Behavioral Health Equity,

which describes the work as: “Advancing health equity involves ensuring that everyone

has a fair and just opportunity to be as healthy as possible. This also applies not only to

behavioral health, but in conjunction with quality services, this involves addressing social

determinants, such as employment and housing stability, insurance status, proximity to

services, culturally responsive care — all of which have an impact on behavioral health

outcomes.”

20

Framework Overview

Harm reduction is practical in its understanding and acceptance that drug use and other

behaviors that carry risk exist ― and responds in a compassionate and life-preserving

manner. Harm reduction seeks to reduce the harmful impacts of stigma, mistreatment,

discrimination, and harsh punishment of PWUD, especially those who are Black,

Indigenous, and other People of Color.

21

Building community partnerships with harm

reduction organizations can positively shape beliefs and attitudes, reduce stigma, and

ensure the well-being of the community at large.

22

Harm Reducon Framework

7

Harm reduction also accounts for the intersection of drug use, other stigmatized behaviors,

and people’s health. Fundamentally, a harm reduction approach meets people where they

are, engaging with them and providing support.

23

Harm reduction opens the door to more options for PWUD, for whom traditional treatment

approaches are inaccessible, ineffective, or inappropriate — and who want to make safer,

healthier choices with their life and health. Access to harm reduction services is consistently

shown to improve individual and community outcomes. By viewing substance use on a

continuum, incremental change can be made, allowing for risk reduction to better suit a

person’s own individual goals and motivations.

Most importantly, harm reduction approaches save lives.

The SAMHSA definition of harm reduction contains six pillars, 12 principles, and six core

practice areas that give life to harm reduction approaches, initiatives, programs, and

services. The pillars are essential building blocks that are the foundation of what makes

harm reduction effective. The pillars are further divided into supporting principles that are the

specific concepts and ideals supporting each pillar. The SAMHSA Framework also describes

the core components of community-based harm reduction programs.

Framing Harm Reduction

SAMHSA conceptualizes harm reduction as being a set of services, an approach, and a

type of organization. Harm reduction has, at times, been reduced to a singular service or

group of services, when in fact, its application goes well beyond this. Harm reduction as

an approach — with supporting principles and pillars that can be applied to a variety of

contexts — includes the provision of evidence-based treatment. An organization or an

individual healthcare practitioner may not consider themselves as primarily providing

harm reduction services but may adopt and apply practices and principles outlined in this

Framework ― to enhance the services they offer and engage with PWUD in a manner

informed by these principles. Any organization who works with PWUD can benefit from the

integration of harm reduction as an approach.

Harm reduction is also part of the continuum of care and a comprehensive strategy that

includes prevention, treatment, recovery, and health promotion. All of these elements are

necessary — and people weigh them differently in different situations, at different points in

their lives, and relative to a wide range of substances and behaviors.

Prevention, in particular primary prevention, seeks to prevent problems before they start.

That means preventing exposure to substances (or screening and intervening with early

misuse), reducing risk factors, and strengthening protective factors at the individual,

relationship, community, and society levels. Prevention also seeks to stop or delay the

progression of substance use to a substance use disorder, as well as prevent other harms

associated with substance use.

Harm reduction recognizes the complex relationship people may have with substances,

starting from first use, through the many possible intervention points from there.

Harm reduction does not minimize the inherent harms associated with drug use and

acknowledges that reducing harm can take different forms for different people at different

points, including with the use of medications to treat substance use disorders. Harm

reduction is also inclusive of abstinence as a chosen pathway but not inclusive of abstinence

as a coerced pathway.

Harm Reducon Framework

8

Harm reduction services must adhere to the harm reduction approach to maintain fidelity

to the evidence base and lead to better outcomes. This is exemplified by the concept of

Community-Based Harm Reduction Programs (CHRPs) described in this Framework.

Pillars of Harm Reduction

Table 1 summarizes the six pillars of harm reduction. Harm reduction initiatives, programs,

or services should include these elements.

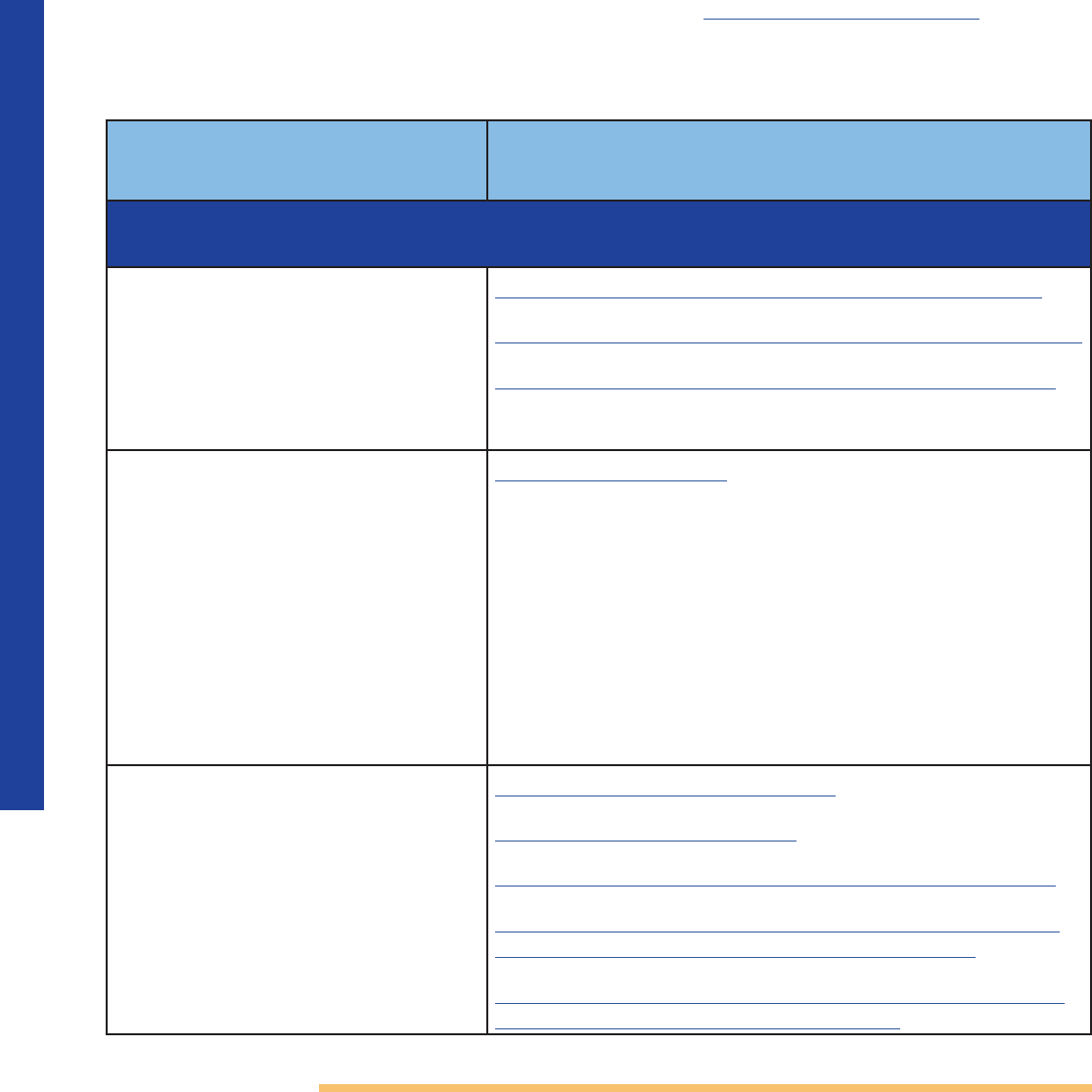

Table 1. Six Pillars of Harm Reduction

Harm Reduction...

1. Is led by people

who use drugs

(PWUD) and

with lived

experience of

drug use

Work is led by PWUD and those with lived and living experience

of drug use. Harm reduction interventions that are evidence

based have been innovated and largely implemented by PWUD.

Through shared decision-making, people with lived experience

are empowered to take an active role in the engagement process

and have better outcomes.

24

Put simply, the effectiveness of harm

reduction programs is based on the buy-in and leadership of the

people they seek to serve.

Organizations providing harm reduction services should have a

formal mechanism to meaningfully include the voices of people

with lived experience in the design, implementation, and evaluation

of those services.

25

Adopting at least two of the following specific

mechanisms of inclusion is mission critical: employment of people

with lived experience in both intervention and administrative roles,

advisory boards of PWUD, and the consultation of CHRPs or any

other peer-led organizations.

It is important to note that while people in recovery and people

who formerly used drugs have valuable experience, centering

the perspectives of people who currently use drugs (and the

intersectionality with other historically marginalized individuals) and

have a working understanding of the current, dynamic, and rapidly

changing landscape of drug use in a particular community in which

an organization is working, is essential to successful engagement

and outcomes. This is exemplified in the provision of OEND

Programs.

26

2. Embraces the

inherent value

of people

All individuals have inherent value and are treated with dignity,

respect, and positive regard.

Harm reduction initiatives, programs, and services are trauma

informed, and never patronize nor pathologize PWUD, nor their

communities. They acknowledge that substance use happens, and

the reasons a person uses drugs are nuanced and complex. This

includes people who use drugs to alleviate symptoms of an existing

medical condition.

Harm Reducon Framework

9

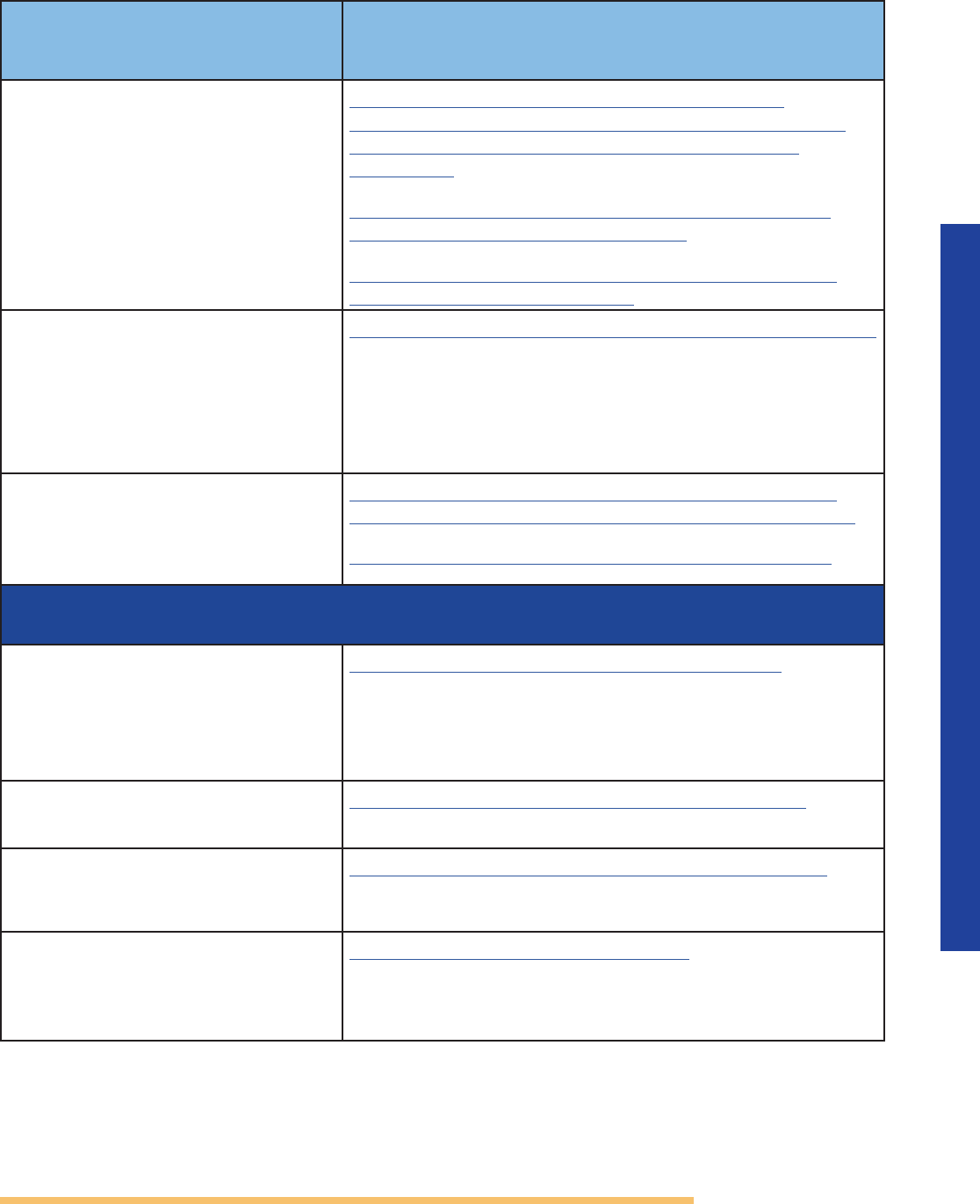

Harm Reduction...(Cont.)

3. Commits

to deep

community

engagement

and community

building

All communities that are impacted by systemic harms are leading

and directing program planning, implementation, and evaluation.

Funding agencies and funded programs support and sustain

community cultural practices, and value community wisdom and

expertise. Agencies and programs develop through community-

led initiatives focused on geographically specific, culturally

based models that integrate language revitalization, cultural

programming, and Indigenous care with dominant-society

healthcare approaches.

4. Promotes

equity, rights,

and reparative

social justice

All aspects of the work incorporate an awareness of (and actively

work to eliminate) inequity related to race, class, language, sexual

orientation, and gender-based power differentials.

Pro-health and pro-social practices that have worked well for specific

cultural and/or geographic communities are aligned with organizing

and mobilizing, providing direct services, and supporting mutual aid

among PWUD.

CHRPs are often the best-placed organizations to respond to

communities or individuals on racial justice and health equity

issues, and provide services for Black, Latino, American Indian and

Alaska Native persons, Asian Americans, Native Hawaiians, and

Pacific Islanders, and other persons of color; members of religious

minorities; LGBTQI+ persons; persons with disabilities; persons who

live in rural areas; and persons otherwise adversely impacted by

persistent poverty or inequality.

5. Offers most

accessible and

noncoercive

support

All harm reduction services have the lowest requirements for access.

Participation in services is always voluntary, confidential (or

anonymous), self-directed, and free from threats, force, and the

concept of compliance. Any data collection requires informed

consent and participants should not be denied services for not

providing information. This means using low-threshold evaluation

and data collection systems to measure the effectiveness of harm

reduction programs.

6. Focuses on any

positive change,

as defined by

the person

All harm reduction services are driven by person-centered positive

change in the individual’s quality of life.

Harm reduction initiatives, programs, and services recognize that

positive change means moving towards more connectedness to

the community, family, and a more healthful state, as the individual

defines it. There are many pathways to wellness; substance use

recovery is only one of them. Abstinence is neither required nor

discouraged.

Harm Reducon Framework

10

Table 2. Principles of Harm Reduction

Supporting

Principles

Principle Description

Respect

autonomy

Each individual is different. It is important to meet people where

they are, and for people to lead their own individual journey. Harm

reduction approaches, initiatives, programs, and services value and

support the dignity, personal freedom, autonomy, self-determination,

voice, and decision making of PWUD.

Practice

acceptance and

hospitality

Love, trust, and connection are important in harm reduction work.

Harm reduction approaches, initiatives, programs, and services hold

space for people who are at greatest risk for marginalization and

discrimination. These elements emphasize trusting relationships and

meaningful connections and understand that this is an important way

to motivate people to find personal success and to feel less isolated.

Provide support Harm reduction approaches, initiatives, programs, and services provide

information and support without judgment, in a manner that is

non-punitive, compassionate, humanistic, and empathetic. Peer-led

services enhance and support individual positive change and recovery;

and peer-led leadership leads to better outcomes.

Connect with

community

Positive connections with community, including family members

(biological or chosen) are an important part of well-being. Community

members often assist loved ones with safety, risk reduction, or

overdose response. When possible, harm reduction initiatives,

programs, and services support families in expanding and deepening

their strategies for love and support; and include families in services,

with the explicit permission of the individual.

Provide many

pathways to

well-being across

the continuum of

health and social

care

Harm reduction can and should happen across the full continuum

of health and social care, meeting whole-person health and social

needs. In networking with other providers, harm reduction initiatives,

programs, and services work to build relationships and trust with

health and social care partners that embrace supporting principles.

To help achieve this, organizations practicing harm reduction utilize

education and encourage policies that facilitate interconnectedness

between all parties.

Supporting Principles

The pillars are supported and reinforced by 12 core principles that guide the work. As with

the pillars, the principles are vital. Programs that do not incorporate all 12 principles risk

violating the spirit of harm reduction.

Harm Reducon Framework

11

Supporting

Principles

Principle Description...(Cont.)

Value practice-

based evidence

and on-

the-ground

experience

Structural racism and other forms of discrimination have limited the

development and inclusion of research on what works in underserved

communities. Harm reduction initiatives, programs, and services

understand these limitations and use community wisdom and

practice-based evidence as additional sources of knowledge.

Cultivate

relationships

Relationships are of central importance to harm reduction. Harm

reduction approaches, initiatives, programs, and services are relational,

not transactional, and work to establish and support quality

relationships between individuals, families, and communities.

Assist, not direct Harm reduction approaches, initiatives, programs, and services support

people on their journey towards positive change, as they define it.

Support is based on what PWUD identify as their needs and goals (not

what programs think they need), offering people tools to thrive.

Promote safety Harm reduction approaches, initiatives, programs, and services actively

promote safety as defined by the people they serve. These efforts

also acknowledge the impact that law enforcement can have on

PWUD (particularly in historically criminalized and marginalized

communities) and provide services accordingly.

Engage first Each community has different cultural strengths, resources,

challenges, and needs. Harm reduction approaches, initiatives,

programs, and services are grounded in the most impacted

and marginalized communities. It is important that meaningful

engagement and shared decision making begins in the design phase

of programming. Equally important is bringing to the table as many

individuals and organizations as possible who understand harm

reduction and who have meaningful relationships with the affected

communities.

Prioritize

listening

Each community has its own unique story that can be the foundation

for harm reduction work. When we listen deeply, we learn what

matters. Harm reductionists engage in active listening ― the act of

inviting people to express themselves completely, recognizing the

listener’s inherent biases, with the intent to fully absorb and process

what the speaker is saying.

Work toward

systems change

Harm reduction approaches, initiatives, programs, and services

recognize that trauma; social determinants of health, such as access

to healthcare, housing, and employment; inequitable policies; lack of

prevention and early intervention strategies; and social support have

all had a responsibility in systemic harm.

Harm Reducon Framework

12

Core Practice Areas

Core practices are effective methods for harm reduction that reflect community

understanding, experience, strengths, and needs. There are six core practice areas: (1)

safer practices; (2) safer settings; (3) safer access to healthcare; (4) safer transitions to care; (5)

sustainable workforce and field; and (6) sustainable infrastructure.

While not an exhaustive list, Table 3 provides key strategies and links to resources.

Anyone in the United States can access free, direct technical assistance (in any of the

core practice areas) from SAMHSA and CDC. SAMHSA’s harm reduction webpage offers

resources, including allowable expenses for its grants that support harm reduction activities.

Table 3. Core Practice Areas

Examples of Practices

Supporting Resources and Evidence

(Research- and Practice-based)

Safer Practices: Education and support describing how to reduce risk; provision of risk

reduction supplies and materials

Needs Based Syringe Services

Programs (SSPs) — also referred

to as syringe exchange programs

(SEPs) and needle exchange

programs (NEPs),* including

secondary exchange.

1,17,19,22,

26

,27,28,29

CDC Syringe Services Programs Technical Package

SAMHSA TIP 33 Treatment for Stimulant Use Disorders

SAMHSA TIP 63 Medications for Opioid Use Disorder

Safer smoking supplies/

distribution to reduce infectious

disease transmission.*

29,30,31

*As permitted by law. No

federal funding is used directly

or through subsequent

reimbursement of grantees to

purchase pipes. Grants include

explicit prohibitions of federal

funds to be used to purchase

drug paraphernalia.

CDC Stimulant Guide

Overdose education, overdose

detection services, and naloxone

distribution.

10,13,26,29,32

CDC Lifesaving Naloxone Guide

SAMHSA What is Naloxone?

SAMHSA TIP 63 Medications for Opioid Use Disorder

SAMHSA Opioid-Overdose Reduction Continuum of

Care Approach (ORCCA) Practice Guide 2023

Engaging Community Coalitions to Decrease Opioid

Overdose Deaths Practice Guide 2023

Harm Reducon Framework

13

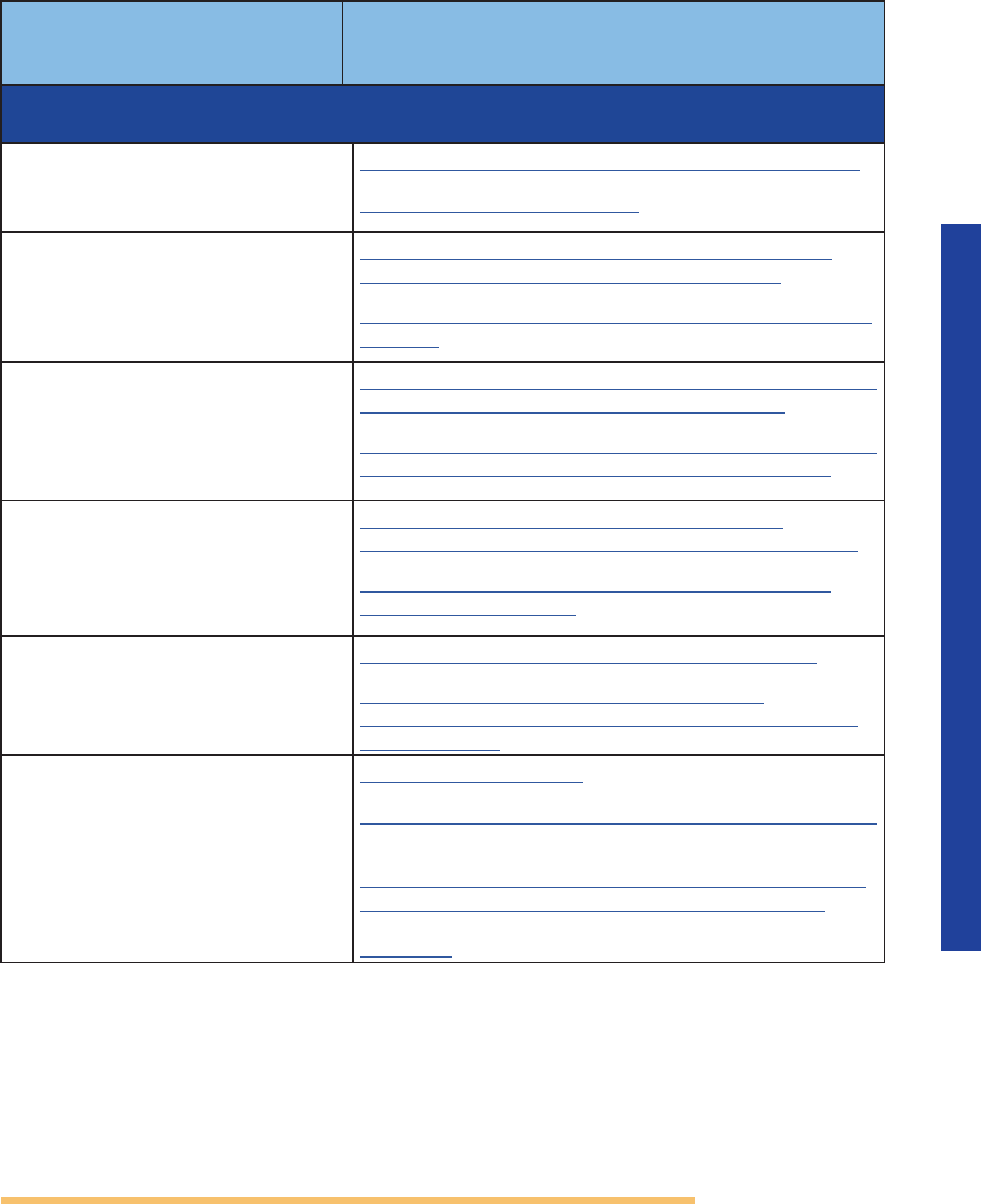

Examples of Practices

Supporting Resources and Evidence

(Research- and Practice-based)...(Cont.)

Drug-checking education,

fentanyl test strips, xylazine

test strips

and other assay test

strips, FTIR spectrometers, and

other drug-checking technology

at community drug-checking

sites.

33,34

CDC MMWR: Rapid Analysis of Drugs: A Pilot

Surveillance System to Detect Changes in the Illicit

Drug Supply to Guide Timely Harm Reduction

Responses

Overdose Data to Action: Surveillance Strategies |

Drug Overdose | CDC Injury Center

SAMHSA Federal Grantees May Now Use Funds to

Purchase Fentanyl Test Strips

Integrated reproductive health

education, services and supplies,

and sexually transmitted infection

screening, prevention, and

treatment.

35,36,37,38

SAMHSA TIP 33 Treatment for Stimulant Use Disorders

Onsite access or immediate

accessible referral to basic wound

care supplies and services in the

community.

38

Wound Care & Medical Triage for People Who Use

Drugs and the Programs That Serve Them | NASTAD

CDC Syringe Services Program Technical Package

Safer Settings: Access to safe environments to live, find respite, practice safer use, and

receive supports that are trauma-informed and stigma-free

Day centers and social spaces

that offer harm reduction

services, are low barrier, and

are led and maintained by the

communities they serve.

39

SAMHSA Peer Support Services in Crisis Care

Access to safe and secure

housing.

33,40

SAMHSA Homeless & Housing Resource Center

Public health programs as

alternatives to arrest and any legal

system involvement.

20,41

SAMHSA Criminal and Juvenile Justice Resources

Hybrid recovery community

organizations providing peer-

delivered harm reduction and

recovery support services.

42

Peer Recovery Center of Excellence

Harm Reducon Framework

14

Examples of Practices

Supporting Resources and Evidence

(Research- and Practice-based)...(Cont.)

Safer Access to Healthcare: Ensuring access to person-centered and non-stigmatizing

healthcare that is trauma informed, including FDA-approved medications

Low-barrier treatment services

that offer a whole-person

approach and rapid re-initiation,

if needed.

43

SAMHSA Practical Tools for Prescribing and Promoting

Buprenorphine in Primary Care Settings

Flexible provision of services

that offer medication starts at

first visit or at home, choice of

medications, and individualized

dosages.

44

SAMHSA Practical Tools for Prescribing and Promoting

Buprenorphine in Primary Care Settings

Healthcare settings and providers

are directly informed by harm

reduction principles, pillars, and

the people they serve.

45,46,47

SAMHSA Engaging Community Coalitions to Decrease

Opioid Overdose Deaths Practice Guide 2023

Nonpunitive care that

consistently offers the standard

of care in a nonstigmatizing,

nonjudgmental manner and

does not refuse healthcare based

on stigma or personal beliefs

about PWUD.

48

Overcoming Stigma, Ending Discrimination

Mobile access and take-home

methadone medication.

49,50,51,52

SAMHSA Methadone Take-Home Flexibilities

Extension Guidance

Mobile buprenorphine services,

including telehealth options

for initiation and continuity of

care.

53,54,55,56

SAMHSA The Physical Evaluation of Patients Who Will

Be Treated with Buprenorphine at Opioid Treatment

Programs

Access to new paradigms of care,

including treatment specific to

the use of all drugs and/or each

drug.

57,58

SAMHSA Treating Concurrent Substance Use Among

Adults

Onsite or quick referral

,

low-

barrier oral health services that

are informed by lived experience

of substance use

.

59

Oral Health, Mental Health and Substance Use

Treatment

Harm Reducon Framework

15

Examples of Practices

Supporting Resources and Evidence

(Research- and Practice-based)...(Cont.)

Safer Transitions to Care: Connections and access to harm-reduction-informed and

trauma-informed care and services

Health hubs for PWUD/ integrated

HIV, viral hepatitis, and healthcare

services.

26,38,60,61,62,63,64

Center of Excellence for Integrated Health Solutions

CDC HIV Risk Reduction Tool

Expand telehealth, while also

addressing low technology

literacy and enhancing access in

languages other than English.

54

SAMHSA Telehealth for the Treatment of Serious

Mental Illness and Substance Use Disorders

SAMHSA Culturally Competent LEP and Low-literacy

Services

Warm hand-off to and from

emergency department programs

― with low-barrier MOUD

initiation and post- overdose

services.

38,65

SAMHSA Connecting Communities to Substance Use

Services: Practical Tools for First Responders

ACA Expanding Access to Medications for Opioid Use

Disorder in Corrections and Community Settings

Medication access and treatment

on-demand (abstinence not

required).

26,66,67,68

SAMHSA Practical Tools for Prescribing and

Promoting Buprenorphine in Primary Care Settings

CDC Linking People with Opioid Use Disorder to

Medication Treatment

Onsite or immediate referral to

accessible nutritional assistance,

clothing, temporary shelter, and

housing.

65

SAMHSA Homeless & Housing Resource Center

SAMHSA Expanding Access to and Use of

Behavioral Health Services for People Experiencing

Homelessness

Seamless coordination of care

for individuals leaving carceral

settings and treatment settings

that do not offer medications,

because people are at greatly

heightened risk for overdose

fatality when back in the

community.

65

SAMHSA GAINS Center

ACA Expanding Access to Medications for Opioid Use

Disorder in Corrections and Community Settings

SAMHSA Best Practices for Successful Reentry from

Criminal Justice Settings for People Living With

Mental Health Conditions and/or Substance Use

Disorders

Harm Reducon Framework

16

Examples of Practices

Supporting Resources and Evidence

(Research- and Practice-based)...(Cont.)

Sustainable Workforce and Field: Resources for maintaining a skilled, well-supported,

and appropriately managed workforce and for sustaining community-based programs

Organizational leadership from

people with living and lived

experience.

26

ASPE Methods and Emerging Strategies to Engage

People with Lived Experience

SAMHSA Participation Guidelines for Individuals with

Lived Experience and Family

NHRC Peer Delivered Syringe Exchange (PDSE)

Toolkit

SAMHSA TIP 64: Incorporating Peer Support into

Substance Use Disorder Treatment Services

Living wages and essential

benefits for harm reduction

workers.

69,70

SAMHSA National Model Standards for Peer Support

Certification

Wellness services and support

for harm reduction staff and

volunteers without mandated

abstinence.

39,71

SAMHSA National Model Standards for Peer Support

Certification

Training and technical assistance

for community-based providers.

38

SAMHSA Practitioner Training

Include harm reduction expertise

and lived expertise in the selection

process of reviewers for harm

reduction grants and other

competitive processes.

72

SAMHSA Grant Review Process

Sustainable Infrastructure:

Resources for building and maintaining a revitalized

and community-led infrastructure to support harm reduction best practices and

the needs of PWUD

Hire and appropriately compensate

PWUD to inform policy at agencies

that serve PWUD.

73

SAMHSA National Model Standards for Peer Support

Certification

Co-leadership of PWUD in

organizational partnership in

research.

74

SAMHSA National Model Standards for Peer Support

Certification

Promote education on the value of

harm reduction services.

26,75, 76,77,78,79

CDC/SAMHSA National Harm Reduction Technical

Assistance Center

SAMHSA Harm Reduction

SAMHSA National Model Standards for Peer Support

Certification

Harm Reducon Framework

17

Community-Based Harm Reduction Programs (CHRPs)

While integrating harm reduction (as an approach and as services) into a wide variety

of settings is beneficial to the people who are served and impacted by them, SAMHSA

is committed to supporting harm reduction organizations that are by and for their

community ― as they are mission critical for connecting to our communities’ most

marginalized individuals.

CHRPs describe harm reduction organizations where people with lived and living

experience lead the planning and oversight, program development and evaluation, and

resource/funding allocation for an organization’s harm reduction initiatives, programs, and

services. CHRPs also offer the core practice areas, as permitted by law. Harm reduction

activities may be integrated into a comprehensive, person-centered program of care that

includes treatment services that meet the specific needs of the community in which the

program is housed.

In addition to programs being consistent with

all aforementioned principles and pillars,

CHRPs should include people with lived experience as co-investigators in any research

project. Boards, staff, and team members should be at least 51 percent those with lived

experience. CHRPs demonstrate meaningful connection to PWUD in their community,

especially to communities most marginalized, and provide lowest-barrier, core harm

reduction practices.

Conclusion

The Harm Reduction Summit was a groundbreaking event that engaged a diversity of

perspectives across the fields of prevention, treatment, recovery, and harm reduction. More

than 100 participants attended the Summit, representing the private sector, community-

based organizations, health care, faith-based organizations, academia, researchers, funders,

law enforcement, and leaders from federal, state, local, and tribal governments.

The subsequent Steering Committee synthesized and refined the Summit findings,

providing guidance for this Framework. Moving forward, this Framework will inform

SAMHSA’s harm reduction activities, as well as related policies, programs, and practices.

SAMHSA’s aim is to integrate harm reduction activities and approaches across its

organizational Centers and initiatives, and to do so in a manner that draws on evidence-

based practice and principles — while also maintaining sustained dialog with harm

reductionists and PWUD.

SAMHSA is committed to continued collaboration with PWUD and the field to put this

Framework into practice, support and expand harm reduction approaches and services,

and ultimately save lives.

Harm Reducon Framework

18

References

1

Abdul-Quader, A.S., Feelemyer, J., Modi, S., & Des Jarlais, D.C. (2013). Effectiveness of structural-

level needle/syringe programs to reduce HCV and HIV infection among people who inject

drugs: a systematic review. AIDS Behavior, 17, 2878–2892. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-013-

0593-y

2

Office of National Drug Control Policy. (2022). National Drug Control Strategy. https://www.

whitehouse.gov/ondcp/the-administrations-strategy/national-drug-control-strategy/

3

Hagan, H., McGough, J.P., Thiede, H., Hopkins, S., Duchin, J., & Alexander, E.R. (2000). Reduced

injection frequency and increased entry and retention in drug treatment associated with

needle exchange participation in Seattle drug injectors. Journal of Substance Abuse

Treatment, 19(3), 247-252. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0740-5472(00)00104-5

4

Haffajee, R.L., Sherry, T.B., Dubenitz, J.M., White, J.O., Schwartz, D., Stoller, B., & Bagalman, E.

(2021). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Overdose Prevention Strategy (Issue

Brief). U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/

documents/101936da95b69acb8446a4bad9179cc0/overdose-prevention-strategy.pdf

5

Des Jarlais, D.C. (2017). Harm reduction in the USA: the research perspective and an archive to

David Purchase. Harm Reduction Journal, 14, Article 51. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-017-0178-6

6

Centers for Disease Control. (1982). Acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS): precautions

for clinical and laboratory staffs. MMWR, 31(43), 577–580. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/

mmwrhtml/00001183.htm

7

McLean K. (2011). The biopolitics of needle exchange in the United States. Critical Public

Health, 21(1), 71–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/09581591003653124

8

The Public Health and Welfare Act, 42 U.S.C. § 300ee-5. (2009). Use of funds to supply

hypodermic needles or syringes for illegal drug use; prohibition. https://www.govinfo.gov/

content/pkg/USCODE-2009-title42/pdf/USCODE-2009-title42-chap6A-subchapXXIII-partA-

sec300ee-11.pdf

9

National Harm Reduction Coalition. (2021). Who we are. https://harmreduction.org/about-us/

10

Wheeler, E., Jones, T.S., Gilbert, M.K., Davidson, P.J., & Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention (CDC). (2015). Opioid overdose prevention programs providing naloxone to

laypersons—United States, 2014. MMWR, 64(23), 631–635. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/

mmwrhtml/mm6423a2.htm

11

Ibid.

12

Ibid.

13

Lambdin, B.H., Bluthenthal, R.N., Wenger, L.D., Wheeler, E., Garner, B., Lakosky, P., & Kral, A.H.

(2020). Overdose education and naloxone distribution within syringe service programs—

United States, 2019. MMWR, 69(33), 1117–1121. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/

mm6933a2.htm

14

Mueller, S.R., Walley, A.Y., Calcaterra, S.L., Glanz, J.M., & Binswanger, I.A. (2015). A review of

opioid overdose prevention and naloxone prescribing: implications for translating community

programming into clinical practice. Substance Abuse, 36(2), 240–253. https://doi.org/10.1080/08

897077.2015.1010032

Harm Reducon Framework

19

15

Aspinall, E.J., Nambiar, D., Goldberg, D.J., Hickman, M., Weir, A., Van Velzen, E., & Hutchinson,

S.J. (2014). Are needle and syringe programmes associated with a reduction in HIV

transmission among people who inject drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis.

International Journal Epidemiology, 43(1), 235–248. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24374889/

16

van Santen, D.K., Lodi, S., Dietze, P., van den Boom, W., Hayashi, K., Dong, H., & Prins, M.

(2023). Comprehensive needle and syringe program and opioid agonist therapy reduce

HIV and hepatitis C virus acquisition among people who inject drugs in different settings: a

pooled analysis of emulated trials. Addiction, 118(6), 1116–1126. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.

gov/36710474/

17

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2019). Summary of Information on the safety and

effectiveness of Syringe Services Programs (SSPs). https://www.cdc.gov/ssp/syringe-services-

programs-summary.html

18

Executive Order No. 13985, 86 Fed. Reg. 7009 (January 20, 2021). Advancing racial equity and

support for underserved communities through the federal government. Federal Register.

https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2021/01/25/2021-01753/advancing-racial-equity-

and-support-for-underserved-communities-through-the-federal-government

19

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). (2022). Community

engagement: an essential component of an effective and equitable substance use

prevention system. SAMHSA. https://store.samhsa.gov/product/community-engagement-

essential-component-substance-use-prevention-system/pep22-06-01-005

20

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). (2022). Behavioral

health equity. SAMHSA. https://www.samhsa.gov/behavioral-health-equity

21

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). (2020). The opioid

crisis and the Black/African American population: an urgent issue. SAMHSA. https://store.

samhsa.gov/product/The-Opioid-Crisis-and-the-Black-African-American-Population-An-

Urgent-Issue/PEP20-05-02-001

22

Zulqarnain, J., Burk, K., Facente, S., Pegram, L., Ali, A., & Asher, A. (2020). Syringe services

program: a technical package of effective strategies and approaches for planning, design,

and implementation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/

cdc/105304

23

Ditmore, M.H. (2013). When sex work and drug use overlap: considerations for advocacy and

practice. Harm Reduction International. https://www.hri.global/files/2014/08/06/Sex_ work_

report_%C6%924_WEB.pdf

24

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). (2010). Shared decision-

making in mental health care: practice, research, and future directions. SAMHSA. https://store.

samhsa.gov/product/Shared-Decision-Making-in-Mental-Health-Care/SMA09-4371

25

Ti, L., Tzemis, D., & Buxton, J.A. (2012). Engaging people who use drugs in policy and program

development: A review of the literature. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy,

7(1), 47–47. https://doi.org/10.1186/1747-597X-7-47

26

Broz, D., Carnes, N., Chapin-Bardales, J., Des Jarlais, D.C., Jones, C.M., McClung, R.P., & Asher,

A.K. (2021). Syringe services programs’ role in ending the HIV epidemic in the U.S.: why we

cannot do it without them. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 61(5, Suppl. 1), S118-S129.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2021.05.044

Harm Reducon Framework

20

27

National Institute on Drug Abuse. (2022). Syringe services programs. https://nida.nih.gov/drug-

topics/syringe-services-programs

28

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). HIV prevention in the United States:

mobilizing to end the epidemic. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/103438

29

Kral, A.H., Lambdin, B.H., Browne, E.N., Wenger, L.D., Bluthenthal, R.N., Zibbell, J.E., & Davidson,

P.J. (2021). Transition from injecting opioids to smoking fentanyl in San Francisco, California.

Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 227, 109003. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34482046

30

Strike, C., & Watson, T.M. (2017). Education and equipment for people who smoke

crack cocaine in Canada: progress and limits. Harm Reduction Journal, 14(17). https://

harmreductionjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12954-017-0144-3

31

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2023). CDC Stimulant Guide. CDC. https://

www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/featured-topics/stimulant-guide.html#q10

32

Weiner, J., Murphy, S.M., & Behrends, C. (2019). Expanding access to naloxone: a review of

distribution strategies. Leonard Davis Institute of Health Economics, Center for Health

Economics of Treatment Interventions for Substance Use Disorder, HCV, and HIV. https://

ldi.upenn.edu/our-work/research-updates/expanding-access-to-naloxone-a-review-of-

distribution-strategies/

33

Park, J.N., Frankel, S., Morris, M., Dieni, O., Fahey-Morrison, L., Luta, M., & Sherman, S. (2021).

Evaluation of fentanyl test strip distribution in two Mid-Atlantic syringe services programs.

International Journal of Drug Policy, 94, 103196. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33713964

34

Peiper, N.C., Clarke, S.D., Vincent, L., Ciccarone, D., Kral, A.H., & Zibbell, J.E. (2019). Fentanyl test

strips as an opioid overdose prevention strategy: Findings from a syringe services program

in the Southeastern United States. International Journal of Drug Policy, 63, 122–128. https://

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30292493

35

Owens, L., Gilmore, K., Terplan, M., Prager, S., & Micks, S. (2020). Providing reproductive health

services for women who inject drugs: a pilot program. Harm Reduction Journal, 17(47). https://

harmreductionjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12954-020-00395-y

36

Burr, C.K., Storm, D.S., Hoyt, M.J., Dutton, L., Berezny, L., Allread, V., & Paul, S. (2014). Integrating

health and prevention services in syringe access programs: a strategy to address unmet

needs in a high-risk population. Public Health Reports, 129(1), 26–32. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.

gov/pmc/articles/PMC3862985

37

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022). HIV risk among persons who exchange sex

for money or nonmonetary items. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/sexworkers.html

38

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2016). Program guidance for implementing

certain components of syringe services programs. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/risk/cdc-hiv-

syringe-exchange-services.pdf

39

Olding, M., Ivsins, A., Mayer, S., Betsos, A., Boyd, J., Sutherland, C., & McNeil, R. (2020). A low-

barrier and comprehensive community-based harm-reduction site in Vancouver, Canada.

American Journal of Public Health, 110(6), 833–835. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32298171/

Harm Reducon Framework

21

40

Watson, D.P., Shuman, V., Kowalsky, J., Golembiewski, E., & Brown, M. (2017). Housing first and

harm reduction: a rapid review and document analysis of the US and Canadian open access

literature. Harm Reduction Journal, 14(30). https://harmreductionjournal.biomedcentral.com/

articles/10.1186/s12954-017-0158-x

41

Volkow, N.D., Poznyak, V., Saxena, S., Gerra, G., & UNODC-WHO Informal International Scientific

Network (2017). Drug use disorders: impact of a public health rather than a criminal justice

approach. World Psychiatry, 16(2), 213–214. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20428

42

Ashford, R.D., Brown, A.M., McDaniel, J., Neasbitt, J., Sobora, C., Riley, R., & Curtis, B. (2019).

Responding to the opioid and overdose crisis with innovative services: the Recovery

Community Center Office-Based Opioid Treatment (RCC-OBOT) model. Addictive Behaviors,

98, 106031. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7286074/

43

Aronowitz, S.V., Navos Behrends, C., Lowenstein, M., Schackman, B.R., & Weiner, J. (2022).

Lowering the barriers to medication treatment for people with opioid use disorder. Leonard

Davis Institute of Health Economics, Center for Health Economics of Treatment Interventions

for Substance Use Disorder, HCV, and HIV. https://ldi.upenn.edu/wp-content/uploads/2022/01/

Penn-LDI.CHERISH-Issue-Brief.January-2022.pdf

44

Jakubowski A., & Fox A. (2020). Defining low-threshold buprenorphine treatment. Journal of

Addiction Medicine, 14(2), 95–98. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC7075734/

45

Hawk, M., Coulter, R.W., Egan, J.E., Fisk, S., Reuel Friedman, M., Tula, M., & Kinsky, S. (2017).

Harm reduction principles for healthcare settings. Harm Reduction Journal, 14, Article 70.

https://harmreductionjournal.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12954-017-0196-4

46

Khan, G.K., Harvey, L., Johnson, S., Long, P., Kimmel, S., Pierre, C., & Drainoni, M.-L. (2022).

Integration of a community-based harm reduction program into a Safety Net Hospital:

A qualitative study. Harm Reduction Journal, 19, Article 35. https://harmreductionjournal.

biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12954-022-00622-8

47

Krawczyk, N., Allen, S.T., Schneider, K.E., Solomon, K., Shah, H., Morris, M., & Saloner, B.

(2022). Intersecting substance use treatment and harm reduction services: exploring the

characteristics and service needs of a community-based sample of people who use drugs.

Harm Reduction Journal, 19, Article 95. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36002850/

48

Muncan, B., Walters, S.M., Ezell, J., & Ompad, D.C. (2020). “They look at us like junkies”:

Influences of drug use stigma on the healthcare engagement of people who inject drugs

in New York City. Harm Reduction Journal, 17, Article 53. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12954-020-

00399-8

49

Chan, B., Hoffman, K.A., Bougatsos, C., Grusing, S., & Chou, R. (2021). Mobile methadone

medication units: A brief history, scoping review and research opportunity. Journal of

Substance Abuse Treatment, 129, Article 108483. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34080541/

50

Greenfield, L., Brady, J.V., Besteman, K.J., & De Smet, A. (1996). Patient retention in mobile and

fixed-site methadone maintenance treatment. Alcohol and Drug Dependence, 42, 125–131.

https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8889411/

51

Frank, D. Mateu-Gelabert, P., Perlman, D.C., Walters, S.M., Curran, L., & Guarino, H. (2021). “It’s

like ‘liquid handcuffs’”: The effect of take-home dosing policies on methadone maintenance

treatment (MMT) patients’ lives. Harm Reduction Journal, 18, Article 88. https://doi.org/10.1186/

s12954-021-00535-y

Harm Reducon Framework

22

52

Amram, O., Amiri, S., Panwala, V., Lutz, R., Joudrey, P.J. & Socias, E. (2021). The impact of

relaxation of methadone take-home protocols on treatment outcomes in the COVID-19 era.

American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 47(6), 722–729. https://www.tandfonline.com/

doi/abs/10.1080/00952990.2021.1979991?journalCode=iada20

53

Rosecrans, A., Harris, R., Saxton, R.E., Cotterell, M., Zoltick, M., Willman, C., & Page, K.R. (2022).

Mobile low- threshold buprenorphine integrated with infectious disease services. Journal of

Substance Abuse Treatment, 133, Article 108553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108553

54

Inheanacho, T., Payne, K., & Tsai, J. (2020). Mobile, community-based buprenorphine treatment

for veterans experiencing homelessness with opioid use disorder: a pilot, feasibility study.

American Journal of Addiction, 29(6), 485–491. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32367557/

55

Krawczyk, N., Buresh, M., Gordon, M.S., Blue, T.R., Fingerhood, M.I., & Agus, D. (2019). Expanding

low-threshold buprenorphine to justice-involved individuals through mobile treatment:

Addressing a critical care gap. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 103, 1–8. https://

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31229187

56

Gibson, B.A., Morano, J.P., Walton, M.R., Marcus, R., Zelenev, A., Bruce, R.D., & Altice, F.L. (2017).

Innovative program delivery and determinants of frequent visitation to a mobile medical

clinic in an urban setting. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 28(2), 643–

662. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28529215

57.

Robbins, J.L., Englander, H., & Gregg, J. (2021). Buprenorphine microdose induction for the

management of prescription opioid dependence. Journal of the American Board of Family

Medicine, 34, S141–S146. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33622829/

58

Randhawa, P.A., Brar, R., & Nolan, S. (2020). Buprenorphine-naloxone “microdosing”: an

alternative induction approach for the treatment of opioid use disorder in the wake of North

America’s increasingly potent illicit drug market. Canadian Medical Association Journal,

192(3). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6970598/#:~:text=Officially%20

recognized%20as%20the%20Bernese,over%20time%20(Box%201).

59

National Council for Mental Wellbeing. (2021). Oral health, mental health and substance

use treatment. https://www.thenationalcouncil.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/NC_CoE_

OralhealthMentalHealthSubstanceUseChallenges_Toolkit.pdf?daf=375ateTbd56&sc_cid=SG_

Refer_blog_mouth-body-connection_link-between-mental-health-and-oral-health

60

Palmateer, N., Hamill, V., Bergenstrom, A., Bloomfield, H., Gordon, L., Stone, & Hutchinson, S.

(2022). Interventions to prevent HIV and hepatitis C among people who inject drugs: latest

evidence of effectiveness from a systematic review (2011 to 2020). International Journal of

Drug Policy, 109, Article 103872. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugpo.2022.103872

61

Rich, K.M., Bia, J., Altice, F.L. et al. (2018). Integrated models of care for individuals with opioid

use disorder: how do we prevent HIV and HCV?. Current HIV/AIDS Reports, 15, 266–275. https://

doi.org/10.1007/s11904-018-0396-x

62

Mette, E. (2020). Q&A: A deep dive into New York’s Drug User Health Hubs with New York’s

Allan Clear. National Academy for State Health Policy. https://www.nashp.org/qa-a-deep-dive-

into-new-yorks-drug-user-health-hubs-with-new-yorks-allan-clear/

Harm Reducon Framework

23

63

Eckhardt, B., Mateu-Gelabert, P., Aponte-Melendez, Y., Fong, C., Kapadia, S., Smith, M.,

Edlin, B. R., & Marks, K.M. (2022). Accessible hepatitis C care for people who inject drugs: a

randomized clinical trial. JAMA Internal Medicine, 182(5), 494–502. https://jamanetwork.com/

journals/jamainternalmedicine/fullarticle/2790054

64

Bartholomew, T.S., Tookes, H.E., Serota, D.P., Behrends, C.N., Forrest, D.W., & Feaster, D.J.

(2020). Impact of routine opt-out HIV/HCV screening on testing uptake at a syringe services

program: an interrupted time series analysis. International Journal of Drug Policy, 84, Article

102875. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32731112

65

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA). (2022). Harm

Reduction. SAMHSA. https://www.samhsa.gov/find-help/harm-reduction

66

Platt, L., Minozzi, S., Reed, J., Vickerman, P., Hagan, H., French, C., & Hickman, M. (2017). Needle

syringe programmes and opioid substitution therapy for preventing hepatitis C transmission

in people who inject drugs. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 9, CD012021. https://

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/28922449/

67

Weinstein, Z.M., Cheng, D.M., D’Amico, M.J., Forman, L.S., Regan, D., Yurkovic, A., Samet,

J.H., & Walley, A.Y. (2020). Inpatient addiction consultation and post-discharge 30-day

acute care utilization. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 213, 108081. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.

drugalcdep.2020.108081

68

Payne, B.E., Klein, J.W., Simon, C.B., James, J.R., Jackson, S.L., Merrill, J.O., Zhuang, R., & Tsui,

J.I. (2019). Effect of lowering initiation thresholds in a primary care-based buprenorphine

treatment program. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 200, 71–77. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.

gov/31103879/

69

Olding, M., Barker, A., McNeil, R., & Boyd, J. (2021). Essential work, precarious labour: the need

for safer and equitable harm reduction work in the era of COVID-19. International Journal of

Drug Policy, 90, Article 103076. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33321286/

70

Greer, A., Bungay, V., Pauly, B., & Buxton, J. (2020). ‘Peer’ work as precarious: A qualitative study

of work conditions and experiences of people who use drugs engaged in harm reduction

work. International Journal of Drug Policy, 85, Article 102922. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.

gov/32911320/

71

Shepard, B.C. (2013). Between harm reduction, loss and wellness: on the occupational hazards

of work. Harm Reduction Journal, 10(5). https://harmreductionjournal.biomedcentral.com/

articles/10.1186/1477-7517-10-5

72

Rittenbach, K., Horne, C.G., O’Riordan, T., Bichel, A., Mitchell, N., Fernandez Parra, A.M., &

MacMaster, F.P. (2019). Engaging people with lived experience in the grant review process.

BMC Medical Ethics, 20, Article 95. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-019-0436-0

73

Marshall, Z., Dechman, M.K., Minichiello, A., Alcock, L., & Harris, G.E. (2015). Peering into the

literature: A systematic review of the roles of people who inject drugs in harm

reduction initiatives. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 151, 1–14. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.

gov/25891234/

74

Brown, G., Crawford, S., Perry, G.E., Byrne, J., Dunne, J., Reeders, D., & Jones, S. (2019). Achieving

meaningful participation of people who use drugs and their peer organizations in a strategic

research partnership. Harm Reduction Journal, 16(1), 37. https://harmreductionjournal.

biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12954-019-0306-6

Harm Reducon Framework

24

75

Fernandez-Vina, M.H., Prood, N.E., Herpolsheimer, A., Waimber, J., & Burris, S. (2020). State laws

governing syringe services programs and participant syringe possession, 2014–2019. Public

Health Reports, 135(S1), 128S–137S. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32735195/

76

Davis, C.S., Burris, S., Kraut-Becher, J., Lynch, K.G., & Metzger, D. (2005). Effects of an intensive

street-level police intervention on syringe exchange program use in Philadelphia, Pa.

American Journal of Public Health, 95(2), 233–236. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/

PMC1449157/

77

Jones, C.M. (2019). Syringe services programs: An examination of legal, policy, and funding

barriers in the midst of the evolving opioid crisis in the U.S. International Journal of Drug

Policy, 70, 22–32. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31059965/

78

Cloud, D.H., Castillo, T., Brinkley-Rubinstein, L., Dubey, M., & Childs, R. (2018). Syringe

decriminalization advocacy in red states: lessons from the North Carolina Harm Reduction

Coalition. Current HIV/AIDS Reports, 15(3), 276–282. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11904-018-0397-9

79

Clark, P.A. & Fadus, M. (2010). Federal funding for needle exchange programs. Medical Science

Monitor, 16(1). https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20037499/

Harm Reducon Framework

25

Harm Reduction Steering

Committee Members

Mark Jenkins

Founder and Executive Director

Connecticut Harm Reduction Alliance

Hartford, CT

Elizabeth Burden

Senior Advisor

National Council for Mental Wellbeing

Phoenix, AZ

Jessica Tilley

Founder

HRH413

Northampton, MA

Hiawatha Collins

Community and Capacity Building Manager

National Harm Reduction Coalition

New York, NY

Sherrine Peyton

State Opioid Settlement Administrator

Illinois Department of Human Services

Chicago, IL

Rafael A. Torruella

Executive Director

Intercambios Puerto Rico

Fajardo, PR

Maya Doe-Simkins

Co-Founder

Harm Reduction Michigan

Traverse City, MI

Chad Sabora

Vice President of Government and Public

Relations

Indiana Center for Recovery

St. Louis, MO

Marielle A. Reataza

Executive Director

National Asian Pacific American Families

Against Substance Abuse

Alhambra, CA

Charles King

Chief Executive Officer

Housing Works

New York, NY

Justine Waldman

Founder and Chief Executive Officer

REACH Medical

Ithaca, NY

Rafael Rivera

Deputy Director

Bureau of Prevention Services, Illinois

Department of Human Services

Chicago, IL

Louise Vincent

Executive Director

North Carolina Urban Survivors Union

Greensboro, NC

Christine Rodriguez

Senior Program Manager

AIDS United

Washington, DC

Philomena Kebec

Economic Development Coordinator

Bad River Tribe

Odanah, WI

Caty Simon

Leadership Team Member

Urban Survivors Union

Holyoke, MA

Stephanie Campbell

Behavioral Ombudsman Project Director

New York State Office of Addiction Services

and Supports

Albany, NY

Anthony D. Salandy

Interim Executive Director, Managing Director

of Programs

National Harm Reduction Coalition

New York, NY

Chase Holleman

Public Health Analyst

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services

Administration (SAMHSA)

Greensboro, NC

Shannon Mace

Executive Director

Legal Assistance Project: A Medical-Legal Partnership

Philadelphia, PA

[This page is intentionally blank.] [This page is intentionally blank.]

[This page is intentionally blank.] [This page is intentionally blank.]

Substance Abuse and Mental Health

Services Administration

SAMHSA’s mission is to lead public health and service delivery eorts that promote mental

health, prevent substance misuse, and provide treatments and supports to foster recovery while

ensuring equitable access and better outcomes.

1-877-SAMHSA-7 (726-4727) • 1-800-487-4889 (TTY) www.samhsa.gov