University of South Carolina University of South Carolina

Scholar Commons Scholar Commons

Theses and Dissertations

Spring 2019

Mental Health and the Relationship Between Parental Divorce and Mental Health and the Relationship Between Parental Divorce and

Children’s Higher Degree Acquisition Children’s Higher Degree Acquisition

Brittany V. Pittelli

Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd

Part of the Sociology Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Pittelli, B. V.(2019).

Mental Health and the Relationship Between Parental Divorce and Children’s Higher

Degree Acquisition.

(Master's thesis). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/5167

This Open Access Thesis is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and

Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact

MENTAL HEALTH AND THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN PARENTAL DIVORCE AND

CHILDREN’S HIGHER DEGREE ACQUISITION

by

Brittany V. Pittelli

Bachelor of Science

University of South Carolina, 2016

Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements

For the Degree of Master of Arts in

Sociology

College of Arts and Sciences

University of South Carolina

2019

Accepted by:

Caroline Hartnett, Director of Thesis

Jennifer Augustine, Reader

Jaclyn Wong, Reader

Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School

ii

© Copyright by Brittany V. Pittelli, 2019

All Rights Reserved.

iii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

There are a number of people I would like to acknowledge for helping me make

this thesis a reality. First, I give my upmost respect and thanks to my committee chair,

Dr. Caroline Hartnett. There were countless emails, office visits, and phone calls that

helped me get to this finishing point. Without Caroline, there is no way this thesis would

have been completed. I would also like to thank my other committee members, Dr.

Jennifer Augustine and Dr. Jaclyn Wong for their support throughout this project.

In addition, I want to thank the University of South Carolina in its entirety for a

wonderful undergraduate and graduate experience. As well as the department faculty for

always having an open-door policy and the colleagues (which became close friends) I

met along the way that kept me motivated throughout my journey.

I would like to say a special thank you to my beautiful mother, Michelle Pittelli as

well as Charles Alagona, for their continuous support and encouragement. Their words

of wisdom kept my spirits high. I’ll always keep in mind that Rome wasn’t built in a day

and only the strong persevere; quitting is never an option. I would not be where I am

without them. Even with the nonstop phone calls listening to me vent, they never let me

give up. Finally, to my lifelong friends and boyfriend, Carly Hansis, Courtney Todd, and

Vincent Olivetti Jr., for their hours of patience, support, and love.

iv

ABSTRACT

Studies between parental divorce and children’s educational attainment have been

extensively observed in family research. However, few studies have attempted to

examine the negative relationship of those associations with graduate level attainment.

This study suggests that parental divorce is associated with diminished overall mental

health (i.e., depressive symptoms) in children, and that this decrease may help explain the

connection between parental divorce and lower graduate level academic attainment.

Using data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1997 (NLSY97), a nationally

representative sample of nearly 9,000 individuals interviewed, this study outlines

hypotheses that link parental divorce, mental health, and graduate level academic success

among children. The results suggest children of divorce are less likely to attain a

graduate degree and are slightly more likely to have depressive symptoms than children

from continuously married parents. There were no significant mediating effects

regarding parental divorce and children’s higher degree acquisition. The findings imply

that the negative effects of divorce may persist past the college years, but that mental

health/emotional resources do not seem to help us understand the relationship between

divorce and the highest levels of educational attainment.

v

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................... iii

ABSTRACT ....................................................................................................................... iv

CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................1

CHAPTER 2: EMPIRICAL AND THEORETICAL BACKGROUND .............................4

Relationship Between Parental Divorce and Educational Attainment .......................4

How Does Depression Shape Educational Indicators/Attainment? ...........................5

Relationship Between Divorce and Depression .........................................................6

What Factors Shape Acquisition of Higher Degrees? ................................................6

Research Questions ....................................................................................................7

Conceptual Model ......................................................................................................8

CHAPTER 3: DATA AND METHODS ...........................................................................10

Variables ...................................................................................................................11

Analytic Strategy ......................................................................................................14

CHAPTER 4: RESULTS ...................................................................................................16

CHAPTER 5: DISCUSSION .............................................................................................23

REFERENCES ..................................................................................................................29

1

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

In the United States, 40-50% of married couples will divorce, leaving 50% of

American children to experience a divorce before the age of 18 (Copen et al., 2012;

Marriage & Divorce, 2019). It is suggested through life course theory that experiences,

which occur early in life, can have long-lasting impressions on a range of situations

throughout a life span (Hayward & Gorman, 2004; Pearlin et al., 2005; Goosby, 2013;

Wickrama et al., 2014). This implies that early life disadvantage, such as family

instability, may create problems that lead to difficulties over the life course (Pearlin et al.,

2005; Schilling et al., 2008; Wickrama et al., 2014). Current research on parental divorce

and its effects on children’s educational experiences have examined childhood and young

adulthood (Cherlin, 2010), with consequences for emotional, behavioral, social, and

academic domains (Amato, 2010). An example of this is children of divorced families

exhibit lower grades and are less likely to attend college (Heard, 2007) as well as higher

antisocial behaviors (Vandewater and Lansford, 1998) than children with continuously

married parents. Compared to children of divorced parents, children in intact families

demonstrate better physical and psychological health outcomes and stronger cognitive

and social competencies (Amato, 2000), which foster better academic performances

(Wallerstein & Lewis, 2004).

Although the studies surrounding parental divorce and children’s educational

attainment have made significant contributions to our understanding, there are still gaps

2

in this research area. Broadly, there is a lack of adequate knowledge of the patterns of

continuing effects of parental divorce during the adult life course (for exceptions see

Björklund & Sundström, 2006; Björklund, Ginther, & Sundström, 2007; Devor et al.,

2018). Specifically, due to the increasing importance of graduate degrees, examining the

effects of parental divorce beyond a bachelor’s degree may be a particularly important

area of study. Colleges today use a less selective process, admitting more diverse and

disadvantaged students than they did in the past. Unlike in the past, a college degree

today does not hold as much weight; there is a need to look beyond a four-year degree for

further stratification. Additionally, little is known about what the mechanisms are that

might result in a lower rate of advanced degree acquisition among children of divorced

parents. A growing body of work examines divorce as a risk factor for children’s well-

being during the formative period of growth, along with other unfavorable life

experiences such as mental health problems (Umberson et al., 2014). Some of the

developmental effects of divorce might be immediately observed, whereas others can be

long-term effects. Divorce is shown to have these long-term effects on a variety of

mental health issues (Ben-Shlomo & Kuh, 2002; Miller, Chen, & Parker, 2011;

Umberson et al., 2014) such as anxiety, depression, attention problems, and aggressive

behavior (Cherlin et al., 1998; Liu et al., 2000; Ross & Mirowsky, 1999). Therefore,

examining the potential mediating role of children’s depressive symptoms may be

especially advantageous.

The purpose of this paper is to assess whether divorce continues to shape

educational achievement beyond college graduation, and if it does, what is the possible

role of depressive symptoms as a mediating factor using a representative sample. A

3

conceptual model is presented that theoretically links parental divorce, mental health, and

children’s graduate level academic success. Several hypotheses drawn from the

conceptual model are tested using data from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth

1997 (NLSY97). The results suggest children of divorce are less likely to attain a

graduate degree and are slightly more likely to have depressive symptoms than children

from continuously married parents. However, there were no significant mediating effects

regarding parental divorce and children’s higher degree acquisition. The findings imply

that the negative effects of divorce may persist past the college years, but that mental

health/emotional resources do not seem to help us understand the relationship between

divorce and the highest levels of educational attainment.

4

CHAPTER 2

EMPIRICAL AND THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

In the current literature, there is adequate support to show that divorce has

negative consequences for children in the short term, but there is less research studying

the effects of divorce on child long-term socioeconomic outcomes such as educational

attainment at the graduate level (Liu, 2007; Bernardi & Radl, 2014). Additionally, little

is known about the mechanisms by which divorce shapes educational outcomes when

dealing with a long time-frame. The long-term consequences of divorce for higher

degree acquisition may be of special importance as education is closely tied to an

individual’s opportunities and life chances (Bernardi & Radl, 2014; Ross & Wu, 1995;

Shavit & Müller, 1998). Obtaining degrees from college and universities helps ensure

economic security, social status, and social mobility (Carnevale & Rose, 2003; Louie,

2007). For example, one study found that college graduates with a bachelor’s degree earn

an average salary of $61,000 over the course of their career, while those with a graduate

degree earn $78,000 annually (Carnevale, Cheah, & Hanson, 2015). Higher education

provides an opportunity for individuals to enhance themselves throughout the life course.

Relationship Between Parental Divorce and Educational Attainment

Research has found that children who experienced parental divorce are at risk for

a variety of negative outcomes, including lower levels of education (Amato, 2010;

Lansford, 2009). There are shorter-term effects of divorce on early education (Amato,

5

2000, 2010; Strohschein, 2005; Sun & Li, 2001, 2011; Vandewater & Lansford, 1998)

and college completion (Black & Sufi, 2002; Bulduc, Caron, & Logue, 2007; Conley,

2001; Perna & Titus, 2005), but less research is done on divorce and graduate attainment

(for exceptions see Björklund & Sundström, 2006; Björklund, Ginther, & Sundström,

2007, Devor et al., 2018). The findings displayed a consistently negative relationship

between parental divorce and children’s educational success (Carlson & Corcoran, 2001;

Cavanagh, Schiller, & Riegle-Crumb, 2006; Frisco et al., 2007; Ginther & Pollack, 2004;

Sun & Li, 2011). This holds true for young children (Amato, 2000; 2005; Amato &

Cheadle, 2005), adolescents (Björklund, Ginther, & Sundström, 2006), and young adults

(Bulduc, Caron, & Logue, 2007; Heard, 2007; Melby et al., 2008; Cavanagh et al., 2006).

For example, Cavanagh et al. (2006) conducted research explaining that the marital

histories of parents can shape a child’s educational achievements throughout the life

course. Their findings highlighted how family instability contributed to stratification in

the United States. In this credential-based economy, graduating from a four-year college

(not to mention graduate school) is found to contribute to better jobs, financial security,

better health and relationships (Cavanagh et al., 2006).

How Does Depression Shape Educational Indicators/Attainment?

Previous research suggests that depression negatively affects academic attainment

(Kessler, 2012; McArdle et al., 2014). It has been found that the prevalence of

depressive symptoms in college students affects almost one-third of the population

(Ibrahim et al., 2013) and might be particularly destructive to higher education in men

(Bohman et al., 2017). Depressive symptoms showed an association with difficulties to

concentrate and complete school tasks (Humensky et al., 2010). Specifically, depressive

6

symptoms of students affect learning ability, academic performance, adaptation to college

life, as well as performance of future professionals (Fröjd et al., 2008).

Relationship Between Divorce and Depression

The main mechanism that I expect will help explain the negative relationship

between divorce and children’s higher-level educational success is depressive symptoms.

This hypothesis is rooted in the family conflict perspective (Amato & Keith, 1991). The

family conflict perspective assumes that inter-parental conflict is a severe stressor for

children, prompting children to experience stress, unhappiness, insecurity, and producing

a negative impact on their psychological adjustment (Amato & Keith, 1991; Bohman et

al., 2017). These psychological effects might continue into adulthood.

There is evidence that shows an ongoing negative effect of childhood parental

divorce on young adult’s mental health (Cherlin, Chase-Lansdale, & McRae, 1998).

Much of the work examining mental health of children with divorced parents shows more

unhappiness, more symptoms of depression and anxiety, less satisfaction throughout the

life course, and greater chance of seeking counseling (Amato & Booth, 1991; Morrison &

Coiro, 1993). Divorce is shown to have long-term effects on a variety of mental health

issues (Ben-Shlomo & Kuh, 2002; Miller, Chen, & Parker, 2011; Umberson et al., 2014)

such as anxiety, depression, attention problems, and aggressive behavior (Cherlin et al.,

1998; Liu et al., 2000; Ross & Mirowsky, 1999).

What Other Factors Shape Acquisition of Higher Degrees?

Research on characteristics of individuals such as race, ethnicity, socioeconomic

status, and gender have been carried out to understand attainment of higher education

7

(Brown, Wohn, & Ellison, 2016; Black & Sufi, 2002; Mullen et al., 2003; Perna, 2000,

2004). For example, low socioeconomic status in childhood is related to poor cognitive

development, language, memory, socio-emotional processing, and consequently poor

income and health in adulthood (Brown et al., 2016). Additionally, there have been a few

studies that tested the relationship between parent’s educational background and graduate

educational attainment of children (Ermisch & Francesconi, 2001; Mullen, Goyette, &

Soares, 2003; Perna, 2004; St. John & Wooden, 2005). The results showed that for each

one-year increase in parents’ background in education, the likelihood for enrollment in a

master’s program increased by 6%, professional programs increased by 16%, and

doctoral programs increased by 20% (Mullen, Goyette, & Soares, 2003). Early life

experiences may also be important for shaping children’s higher education (Center on the

Developing Child, 2011).

Research Questions

Although there is substantial literature on the effects of divorce on children and

adolescents, information about the long-term effects of divorce after the transition to

adulthood is less comprehensive. Similarly, little is known about the factors shaping

advanced degree acquisition, including how family dynamics and mental health shape

whether or not people obtain advanced degrees. Therefore, the main research questions

for this project are:

1) Is parental divorce related to higher degree acquisition?

2) Does depression in young adulthood mediate the relationship between

parental divorce and higher degree acquisition?

8

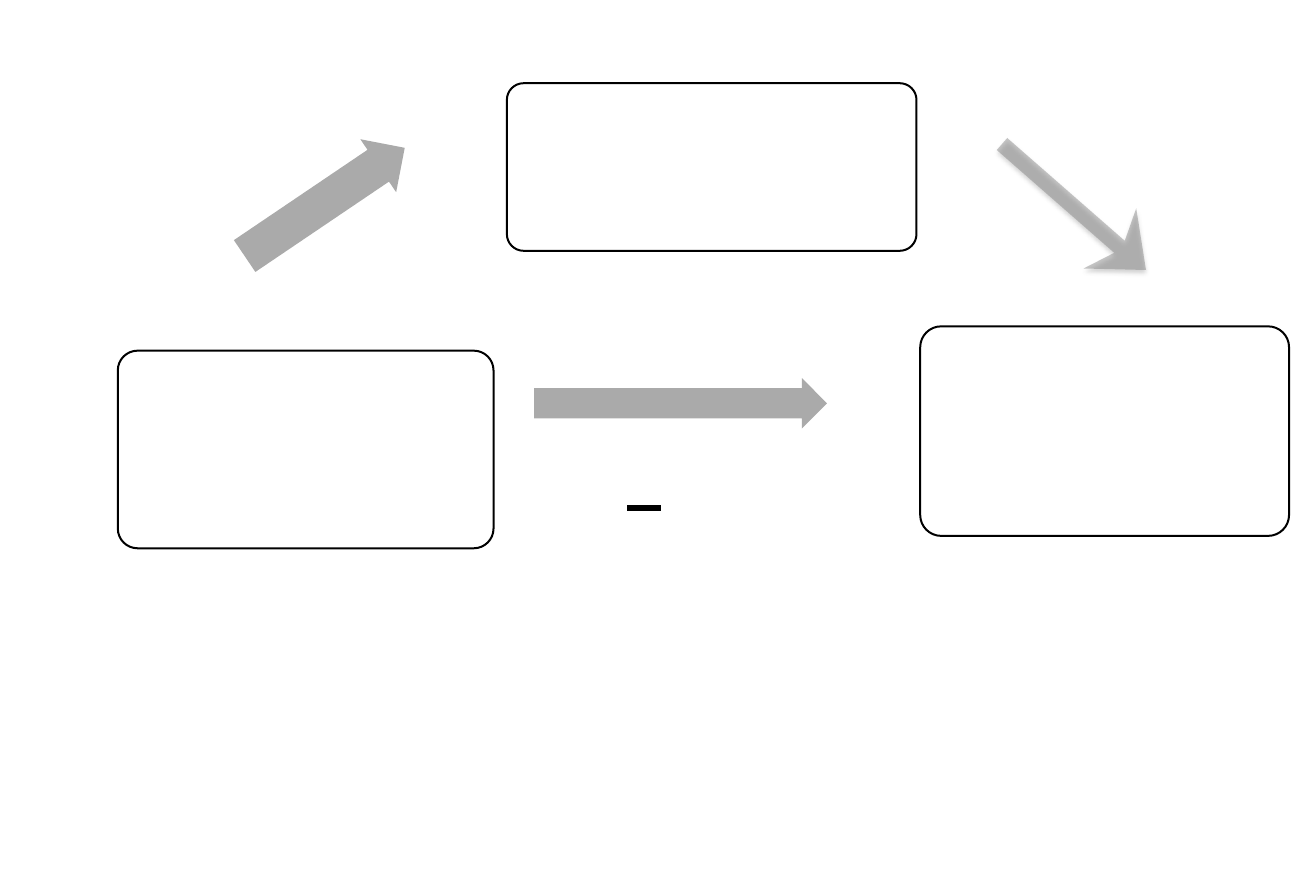

Conceptual Model

Centered around the theoretical framework and research examined above, I

present one conceptual model, which includes two pathways on the way(s) in which

parental divorce and depressive symptoms may be linked to children’s graduate level

educational success. The model shows a direct effect of parental divorce negatively

impacting children’s graduate level academic achievement (path A). The model also

suggests that depressive symptoms may serve as a mediator between parental divorce and

educational attainment of their children, such that the effect of parental divorce will be

explained in part or fully (path B). This conceptual model can be seen in Figure 2.1.

9

Parental Divorce

Children's Graduate Educational

Attainment

Depressive Symptoms

Figure 2.1: Conceptual framework of parental divorce, children’s graduate educational attainment, and the

possible mediating effects of depressive symptoms.

(B)

+/-

(A)

10

CHAPTER 3

DATA AND METHODS

Data for the present study came from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth

of 1997 (NLSY97). Produced by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the NLSY97 data

are collected on respondents born between 1980 and 1984. At the time of the first

interview (Round 1, 1997), respondents’ ages ranged from 12 to 18. In Round 1 (1997),

there was a nationally representative sample of nearly 9,000 individuals interviewed

(8,984). In this round, both the respondent and one of that youth’s parents (responding

parent) received hour-long personal interviews (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2006). In

addition, an extensive two-part questionnaire was administered to both youth and parent.

Round 1 was the only round the parents were interviewed. The children, not their

parents, were interviewed on an annual basis after Round 1.

The most recent data release is Round 17 fielded in 2015-2016. At the time of the

Round 17 interviews, respondents were 30-36 years of age. Round 17 yielded 7,103

respondents, or approximately 80 percent of the original Round 1 respondents (National

Longitudinal Surveys, 2018). The NLSY97 is a good fit for the present study for its

focus on the transition from school to work in young adulthood (Bureau of Labor

Statistics, 2006). It collects extensive data on demographic information, employment

information, educational experiences, relationship with parents, marital and fertility

histories, dating, criminal behavior, alcohol and drug use, mental health/depression, etc.

11

Variables

Highest Degree Received: The key outcome variable of educational attainment

was assessed at Round 17 (2015) of the survey. The respondents were asked, “What is

the highest educational degree [respondent] has ever received?” The following were the

responses: (a) none, (b) GED, (c) high school diploma, (d) Associate/Junior college, (e)

Bachelor’s degree, (f) Master’s degree, (g) PhD, and (h) Professional degree.

Dichotomous variables were created that measured whether or not the youth obtained a

Bachelor’s degree or higher, as well as whether or not the youth received a

graduate/professional degree.

Parental Divorce: Parental divorce was measured by combining multiple

variables in the NLSY97. From the parent questionnaire, the responding parent’s marital

history collected information on the length of each marriage as well as any changes in the

marital status (i.e. legal separation, divorce) for each marriage. If the responding parent

had been married, he/she answered “In what month and year did you marry [this

spouse/partner]?” for up to six spouses. For each of those marriages, the responding

parent was asked, “Are you currently separated, divorced, or widowed from that spouse?”

If the responding parent answered “yes,” the following question was “How did the

marriage to spouse(s) end?” The four categories were (1) legal separation only (2)

physical separation but no legal separation (3) divorce and (4) death for up to five

spouses. The responses of legal separation only, physical separation but no legal

separation, and death were removed from the sample. If the answer was “divorce,” the

responding parent was asked in what month and year did the divorce take place for up to

4 divorces. The responding parent was also asked if he/she had been continuously

12

married or not for up to six spouses. In order to determine if the youth were born within

a marriage, the youth’s birthdate would need to fall between the spouses’ start and end

date of their marriage. A dichotomous variable of divorced was calculated for whether

parents of the child ever divorced (versus marriages that remained intact).

To try and capture youth who had parents that divorced after Round 1, the youth

were asked if their biological parents had divorced within the previous 5 years (assessed

at Rounds 6, 11, 12, 13, and 16). Round 6, which had children aged 17-23, was used to

identify the children who were 17 or 18 at the time of their parents’ divorce. Only

divorces that happened when the child was 18 or younger were counted.

Depressive Symptoms: Depressive symptoms were measured using five questions

derived from a short version of the Mental Health Inventory (MHI-5), developed by Veit

and Ware in the early 1980s (Veit & Ware, 1983). These were taken in 2015 from the

most current round (17) of the NLSY97 depression scale to measure respondent’s current

depression. Respondents were asked how often in the past month they: (1) felt depressed,

(2) been a very nervous person, (3) felt downhearted and blue, (4) felt calm and peaceful,

and (5) been a happy person. Responses ranged from “(0) none of the time, (1) some of

the time, (2) most of the time, and (3) all of the time.” Positive responses were reverse

coded, and the five items were summed with a range of 0 to 15, with higher scores

corresponding to higher levels of depressive symptoms (Wickrama et al., 2014; Radloff,

1977; Foster et al., 2008). The Cronbach’s alpha = 0.80. Depressive symptoms were

also split up into low (0-4), medium (5-9), and high (10-15) categories to test for

significance using chi-squared tests.

13

Controls for Youth Characteristics: Youth characteristics were taken from Round

1 of the youth questionnaire in the NLSY97. The gender was coded dichotomously as

male and female, with male serving as the reference category. Age was measured in

years. Race and ethnicity were measured at Round 1 and were coded as White (non-

Hispanic), Black/African American (non-Hispanic), Hispanic, and Other (non-Hispanic).

White serves as the reference category.

Controls for Parent Characteristics: The educational background is based on a

Round 1 question asking for the highest grade completed by respondent’s biological

mother and biological father. Based on this, parental educational background was

recoded as (1) high school or less, (2) some college, (3) bachelor’s/4-year college degree,

and (4) graduate/professional degree. A set of dummy variables was created for each

category of education for mothers and fathers, with high school or less serving as the

reference category.

Controls for Household Characteristics: In Round 1, the child’s parents reported

household income for the most recent year. The NLSY97 defined income as gross

wage/salary for respondent, along with data on other income sources (rental property,

small business investments, inheritance, child support, annuities, etc.) (U.S. Bureau of

Labor Statistics, 2014). To reduce the proportion of missing data, respondents who do

not provide exact dollar answers were asked to select the applicable category from a

predefined list of ranges. Based on these predefined ranges, a variable was created based

on income terciles: (1) low (less than or equal to $23,100), (2) medium (more than

$23,100 but less than or equal to $51,400), and (3) high (more than $51,400) with high

income serving as the reference category.

14

Analytic Strategy

Data analysis progressed in several steps. First, the analytic sample was

comprised of respondents who completed Round 17 of the survey, when respondents

were between the ages of 30-36 (N=8,984). The sample was limited to youth whose

parent questionnaire was filled out by a biological parent, either the biological mother or

the biological father, following other research (Devor et al., 2018; Lansford, 2009;

Bulduc, Caron, & Logue, 2007). Due to most of the divorce data coming from biological

parents, youth whose parent questionnaire was filled-out by an adoptive, step, foster,

guardian or non-relative parent were removed from the sample (N=8,300) (Carlson &

Corcoran, 2001; Gennetian, 2005; Ginther & Pollack, 2004; Wallerstein & Lewis, 2004).

The sample was also limited to children who were born within a marriage between their

biological parents, thus youths born outside of a marriage were removed from the sample

(N=5,202). Finally, the sample was limited to having biological parents either end in a

legal divorce or have been continuously married, meaning that children whose parents

separated, never chose to marry, or died were dropped (N=4,984). These sample

limitations follow those made in similar research on divorce and educational attainment

(Devor et al., 2018). All variables, with the exception of respondent’s highest degree

received and depressive symptoms will be measured using Round 1 of the survey; highest

degree received and depressive symptoms are measured with Round 17, the most current

year of the survey (2015). Descriptive statistics for each variable used in the analysis are

reported and assessed for the analytic sample (see Table 4.1).

Bivariate relationships between parental divorce and key variables (particularly

depressive symptoms and higher degree acquisition) were assessed using chi-squared

15

tests. Finally, mediation analyses were conducted using the binary_mediation command

in Stata 14. I examined the association of the full sample between parental divorce and

children’s graduate level academic attainment, with depressive symptoms as a mediator.

Depressive symptoms were coded as a continuous variable in these analyses.

Binary_mediation can be used with multiple mediator variables in any combination of

binary or continuous along with either a binary or continuous response variable. This

command provided the indirect effect (of parental divorce on higher degree acquisition

via depressive symptoms), direct effect (i.e., remaining effect that is not explained by the

mediator), and total effect (i.e., parental divorce on higher degree acquisition) of

depressive symptoms as a mediator between parental divorce and children attaining a

graduate degree. The command binary_mediation does not produce standard errors or

confidence intervals. Therefore, the bootstrap command was used and obtained standard

errors for the direct and indirect effects along with a 95% percentile confidence intervals.

The results are interpreted as significant when the confidence interval does not contain

zero. I estimated the model twice. In Model 1, the sample included the full sample of

youth. Model 2 was limited to if the youth graduated from college with at least a 4-year

degree.

16

CHAPTER 4

RESULTS

Descriptive statistics for the overall sample are presented in Table 4.1. For the

sample, 62% of the youth had received less than a Bachelor’s degree, compared to

approximately 26% of youth who completed a Bachelor’s/4-year college degree. Only

12% of youth obtained a graduate degree. On average, 64% of respondents reported

relatively low (scale of 0-4) levels of depressive symptoms versus 33% of medium (scale

of 5-9) and 3% of high (scale of 10-15) levels of depressive symptoms. Regarding family

structure, 28% of youth had divorced parents (that occurred before age 18) compared to

78% of youth who had both biological parents remain married. In terms of

sociodemographic characteristics for the overall sample, 52% were men and 48% were

women with the average age being around 33. Approximately two-thirds of the sample

was white. In addition, the youth’s parents’ educational background indicated the

majority of parents (mothers (50%) and fathers (53%)), had a high school education or

less. Lastly, in terms of household income, only about 19% were in the lowest third (less

than or equal to $23,100), versus 45% of the households were in the highest third (more

than $51,400).

Table 4.1 also presents the bivariate relationship between youth’s family

structure, depressive symptomology, and their educational attainment. Many significant

differences emerge between youth with divorced biological parents and youth with

continuously married biological parents. A higher proportion of youth with parents who

17

remained married attained a graduate degree (13%) compared to youth with divorced

parents (8%). A lower percentage of youth with divorced parents had a Bachelor’s

degree (17%) than youth with parents who remained continuously married (29%).

Depressive symptoms were rather alike for children who had divorced parents, but were

still significantly different; the low category with a range of 0-4 (58%), medium with a

range of 5-9 (38%), and high with a range of 10-15 (4%) compared to children with

continuously married parents that had low (66%), medium (32%), and high (2%)

categories. With respect to parental educational background, the percentage of parents

with high school education or less and some college was relatively similar for parents

who had ever divorced versus parents who remained continuously married. Finally, a

much higher proportion of youth with continuously married parents had higher childhood

household income versus youth with divorced parents.

Table 4.2 presents the mediation analysis results of the association between

parental divorce, depressive symptoms, and children’s higher degree acquisition. The

covariates controlled for in the models were gender, age, race/ethnicity, parents’

educational background, and household income. The top section of the table shows

results for the full group of respondents. The analysis confirms that parental divorce does

predict children to be disadvantaged in attaining graduate degrees (total effect). The

mediation results (indirect effect 1) indicate that depressive symptoms do not mediate the

association between parental divorce and children attaining a graduate degree.

The bottom section of Table 4.2 is limited to youth with at least a bachelor’s/4-

year degree. These results indicate parental divorce also predicts children to be

disadvantaged past completion of a bachelor’s/4-year degree. The analysis did show a

18

significant mediation effect for children with at least a bachelor’s/4-year degree. The

effect is small and only 1.3% of the total effect is accounted for by depressive symptoms.

This percentage was found using binary_mediation and is explained as proportion of total

effect mediated. Parental divorce was negatively associated with the odds of obtaining

graduate degrees after accounting for gender, age, race/ethnicity, parents’ educational

background, and household income, but depressive symptoms among children with

divorced parents do not fully explain the negative effects of parental divorce.

19

Table 4.1. Descriptive Statistics on Analytic Sample and Bivariate Relationship Between Parental Divorce and Children’s

Educational Attainment (4,984)

All

Parents ever divorced

Parents continuously married

(N=4,984)

(N=1,388)

(N=3,596)

Variables

Percent

Percent

Percent

Chi-square

Highest Degree Received

104.48***

Less than Bachelor's Degree

62.26

74.95

57.3

Bachelor's, no Graduate Degree

25.75

16.82

29.24

Graduate Degree

11.99

8.23

13.46

Depressive Symptoms

25.58***

Low (0-4)

64.07

58.31

66.3

Medium (5-9)

33.31

37.75

31.59

High (10-15)

2.62

3.94

2.11

Gender of youth

7.8**

Male

51.52

48.34

52.75

Female

48.48

51.66

47.25

20

Age

30-36

32.91

−

−

Race/ethnicity of youth

52.32***

White

66.75

67.15

66.6

Black

12.9

17.36

11.18

Hispanic

19.64

15.05

21.41

Other

0.7

0.43

0.81

Mother's education

35.47***

High school or less

50.45

48.95

51.02

Some college

26.07

31.54

23.96

Bachelor's Degree

14.55

11.58

15.69

Graduate/professional degree

8.94

7.92

9.33

Father's education

110.01***

High school or less

53.05

65.28

48.91

Some college

20.83

19.01

21.44

Bachelor's Degree

14.59

9.03

16.47

21

Graduate/professional degree

11.53

6.68

13.18

Household income

312.78***

Low (≤$23,100)

18.83

31.32

13.74

Medium ($23,101≤ $51,400)

36.44

43.64

33.51

High ($51,400)

44.72

25.04

52.75

Note: Data comes from National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1997; Reference categories are “male,” “White,” “high school or less”

(mother/father), and “high” income (≤$246,500); *p<.05; **p<.01; ***p<.001.

Table 4.2. Mediation Analysis Results of the Association Between Parental Divorce and Children’s Higher Degree Acquisition

with Depressive Symptoms as a Mediator

Depressive

Symptoms

Effects

Paths

Coef.

95% C.I.

a

Y1: Graduate Degree

Indirect Effect

(parental divorce→depressive symptoms→graduate

degree)

-0.003

(-0.007; 0.0014)

Direct Effect

(parental divorce (depressive symptoms)→graduate

degree)

-0.085

(-0.167; -0.01)

22

Total Effect

(parental divorce→graduate degree)

-0.087

(-0.165; -0.0095)

Y2: Grad degree,

limited to BA

completion

Indirect Effect

(parental divorce→depressive symptoms)→ graduate

degree)

-0.005

(-0.008; -0.001)

Direct Effect

(parental divorce (depressive symptoms)→graduate

degree)

-0.023

(-0.034; -0.0113)

Total Effect

(parental divorce→graduate degree)

-0.021

(-0.030; -0.0113)

Note: Bootstrapping results after 500 replications;

a

bias-corrected confidence intervals using the binary_mediation command in Stata;

Bold if the result is significant at least at the .05 level of significance; gender, age, race/ethnicity, parents’ educational background,

and household income are controlled for in all models.

23

CHAPTER 5

DISCUSSION

Life course theory proposes that early life difficulties may have harmful effects

while moving through the life course (Hayward et al., 2004; Pearlin et al., 2005; Goosby,

2013; Wickrama et al., 2014). These difficulties, particularly early family instability, can

lead to damaging consequences for mental health, such as depressive symptoms, in

adulthood (Schafer et al., 2011; Wickrama et al., 2014). Although the negative effects of

parental divorce on children’s educational attainment and mental health has been constant

in former studies, there has been little examination regarding young adults with higher

degree acquisition and the factors that may be working to explain the lower rate of

advanced degrees among children of divorce. The two key contributions of the present

study were (a) including a measure of advanced educational attainment (i.e., achieved a

graduate degree); and (b) examining whether depression plays a significant role in

mediating the negative relationship between parental divorce and higher degree

acquisition in a nationally representative sample.

The results of the present study addressed the potential negative influence of

parental divorce and children’s graduate level educational success. An examination of the

bivariate results provides strong support for the first research question showing that

young adults with divorced parents were less likely to achieve a graduate degree

compared to children with continuously married parents. These results support previous

research on U.S. families indicating that children with divorced parents are educationally

24

disadvantaged in terms of both completions of a bachelor’s degree and

graduate/professional degrees. This extends our knowledge of parental divorce and

children’s educational outcomes beyond childhood and adolescence (Ginther & Pollack,

2004; Wallerstein & Lewis, 2004) showing adults exhibit long-term deficits in

functioning from marital dissolution (Amato, 2000). This is consistent with research on

adults of divorce experiencing disrupted interpersonal relationships that has shown they

tend to marry early, experience unhappy marriages, divorce repeatedly, generally mistrust

people, and feel limited on their social support (Ross & Mirowsky, 1999). Even 30 years

after the time of the divorce, negative long-term consequences still clearly affect income,

education, health, and behavior of many grown children (Uphold-Carrier & Utz, 2012).

Furthermore, possessing a graduate degree is becoming increasingly important to one’s

economic success. Having a Master’s, Professional, and/or Doctoral degrees have

become a requirement for entry into many professions, can give success in the

competitive job market, and is strongly related to income (Thomas & Zhang, 2005). Jobs

requiring a master’s degree are expected to grow by nearly 17 percent between 2016 and

2026 (Bureau of Labor Statistics, 2016). In light of the increasing importance of graduate

education, the long-term effects of divorce may continue to affect future socioeconomic

inequalities in the United States. Lower socioeconomic status adults are more likely to

divorce or to never marry than are higher socioeconomic status adults (Cherlin et al.,

2010) leading divorce to potentially limit future social mobility.

I also examined whether depressive symptoms mediated the relationship between

parental divorce and children’s higher degree acquisition and found that they did not.

This suggests that the negative effects of parental divorce may persist past the college

25

years even after accounting for the negative impact on children’s mental health. These

emotional resources do not seem to help us understand that relationship. Depressive

symptoms were not an important mediator, (even though it was statistically significant in

the second set of models by only 1.3%). There are several alternative possibilities, which

could be explored in future research. Firstly, financial instability is one of the more

prominent effects experienced by children from non-traditional family structures.

Although an increasing number of parents share legal custody after divorce, the majority

of children live primarily with their mothers (Fox & Kelly, 1995; Hardesty & Chung,

2006). The increasing costs of higher education can become a deterrent for children of

divorce, even with federal financial assistance. Financial resources might help explain

the gap in educational attainment, even though income was controlled for in the models.

However, the income measure used was very unrefined. Parents’ accumulated wealth

differs across family structures, affecting the amount of financial support for higher

education. Divorced parents (36%) are less likely to pay for all or most of their

children’s higher education, compared to married parents (59%) (Amato et al., 1995).

Additionally, divorced parents are more likely than married parents to provide no

assistance for higher education at all (Amato et al., 1995). Secondly, arguments have

been made about the consequences of divorce for parenting styles and quality. It is well

known that children of divorce experience a decrease in parental attention, help, and

supervision (Amato & Keith, 1991), which may increase the likelihood of problems for

children, such as academic failure (Bernardi & Radl, 2014). Parents now give more

support to grown children, on average, than parents gave in the past (Fingerman et al.,

2012). Some scholars have suggested that over a third of the financial costs of parenting

26

occur after the age of 18 (Mintz, 2015). In addition to financial support, time is also

given to grown children through their parents by helping to make doctor’s appointments,

offering emotional support, or giving advice (Mintz, 2015). These differences in

emotional and non-tangible supports from divorced versus married parents could help to

explain the educational gap, even for advanced degrees. Finally, children who

experience their parents’ divorce are likely to have had extended exposure to conflict

between their parents, diminishing children’s capacity to handle conflict (Billingham &

Notebaert, 1993). This conflict is distressing for children and can have long-term effects

on educational attainment (Amato, 2005), contributing additional instability during a time

that is already marked with uncertainty and possibly upsets a child’s ability to learn

(Mehana & Reynolds, 2004). Compared to children from continuously married families,

college students from divorced families have lower educational aspirations and are less

educated into adulthood (Gruber, 2004). For example, adult children of divorce may

externalize their distress in the form of aggression, hostility, non-compliant behavior,

delinquency, and vandalism, or internalize it in the form of depression, anxiety,

withdrawal, and dysphoria (Sutherland, 2014) affecting educational attainment. As

college and graduate attendance is becoming more common, more work is needed to

theorize and model explanations beyond life course theory and mental health for

understanding graduate academic success. This study is important for adding to the

current baseline that future research can draw upon.

There are several important limitations to note of the present study. These

limitations highlight important future directions. First, the main focus was solely on

parental divorce and did not add in separation or couples who never chose to get married.

27

This excludes other prevalent non-traditional family structures. However, research on the

effect of parental divorce on graduate level attainment is relatively new and not fully

understood yet, establishing the present study as an important baseline that can be drawn

upon in future research. Second, there are certain event-ordering issues. Ideally, we

would want to isolate situations in which: the parental divorce precedes depressive

symptoms, and depressive symptoms precede enrolling in graduate school. I was able to

line up ordering for parental divorce occurring prior to testing for depressive symptoms.

Only divorces that happened by the time children were 18 counted as divorce for the

study. I used the most recent measures of depressive symptoms from the NLSY97 to

ensure that they took place close to the time at which respondents would have been in

graduate school. Lastly, only five variables were available in the NLSY97 to construct

the depression scale to create an index of depressive symptomology. This scale is

known, as the Mental Health Inventory (MHI-5) and is the subscale of the Mental Health

Inventory-38. The validity and reliability may have been increased, had there been

access to the full scale on the NLSY97. The full scale of the MHI has a Cronbach’s alpha

of 0.93, while the subscale has an alpha of 0.82 (Mental Health Inventory, 2019).

However, there is enough faith in the 5-measure item to be using it in this study because

it has been extensively examined in large populations and has evidence for its validity

(Mental Health Inventory, 2019).

Future research should examine differing familial structures on children’s

graduate school enrollment and degree attainment, which could include cohabiting, same-

sex coupling, intergenerational households, stepfamilies, etc. This research has already

been carried out examining differing familial structures and children’s bachelor degree

28

attainment. For example, 36% of children from married parents received a bachelor’s

degree, 20% of cohabiting families, and 16% of stepfamilies (Fagan & Talkington, 2004).

Examining the potential differences between bachelor and graduate degrees would also

be valuable, considering the mindset, coursework, and environment that accompany both

(Franklin University, 2019). Additionally, graduate degrees can open doors to

opportunities (i.e., promotions and raises) that might not be available without it (Franklin

University, 2019). Most children rely on their families and student loans to pay for

college costs (FinAid, 2019). Specifically, due to the increasing importance of graduate

degrees, examining the effects of parental divorce beyond a bachelor’s degree shows to

be a particularly important area of study. Furthermore, future studies should focus on

how the costs of higher education can become a burden for children of divorce. This

thesis provides an important glimpse of the consequences of parental divorce on

children’s graduate-level attainment. Specifically, adding to the previous work

surrounding life course theory and the effects of parental divorce on mental health and

education broadly, while also enhancing to the literature regarding the mediating effects

of depressive symptoms. As long as nearly half of marriages in the United States end in

divorce and children continue to view higher education as a foundation to their future

success, there will be a long-term need to understand and monitor the higher educational

consequences of marital dissolution.

29

REFERENCES

Amato, P. R., & Keith, B. (1991). Parental divorce and Adult-Well-Being: A Meta-

Analysis. Journal of Marriage and Family 53: 43-58.

Amato, P. R., & Keith, B. (1991). Parental Divorce and the Well-Being of Children: A

Meta-Analysis. Psychological Bulletin 110(1): 26−46.

Amato, P. R. (2000). The Consequences of Divorce for Adults and Children. Journal of

Marriage and Family 62(4): 1269–1287.

Amato, P. R. (2005). The impact of family formation change on the cognitive, social, and

emotional well-being of the next generation. The Future of Children, 15(2): 75-

96.

Amato, P. R., & Cheadle, J. (2005). The long reach of divorce: Divorce and child well-

being across three generations. Journal of Marriage and Family, 67: 191-206.

Amato, P. R. (2010). Research on Divorce: Continuing Trends and New Developments.

Journal of Marriage and Family 72(3): 650−666.

Amato, P. R., & Booth, A. (1991). Consequences of parental divorce and marital

unhappiness for adult well-being. Social Forces, 69(3): 895-914. Beck, A.,

Cooper, C., McLanahan, S., and Brooks-Gunn, J. (2010). Partnership Transitions

and Maternal Parenting. Journal of Marriage and Family 72(2): 219-233.

30

Amato, R. R., Rezac, S. J., & Booth, A. (1995). Helping Between Parents and Young

Adult Offspring: The Role of Parental Marital Quality, Divorce, and Remarriage.

Journal of Marriage and Family, 57: 373.

Ben-Shlomo, Y. & Kuh, D. (2002). A life course approach to chronic disease

epidemiology: conceptual models, empirical challenges, and interdisciplinary

perspectives. International Journal of Epidemiology, 31(2): 285-293.

Bernardi, F. & Radl, J. (2014). The Long-Term Consequences of Parental Divorce for

Children’s Educational Attainment. Demographic Research 30: 1653-1680.

Billingham, R. E. & Notebaert, N. L. (1993). Divorce and Dating Violence Revisited:

Multivariate Analyses Using Straus’s Conflict Tactics Subscores. Psychological

Reports, 73: 679-684.

Björklund, A., & Sundstrom, M. (2006). Parental separation and children’s educational

attainment: A siblings analysis on Swedish register data. Economica, 73: 605-624.

Björklund, A., Ginther, D. K., & Sundstrom, M. (2007). Family structure and child

outcomes in the USA and Sweden. Journal of Population Economics, 20: 183-

201.

Black, S. E., & Sufi, A. (2002). Who goes to college? Differential enrollment by race and

family background. NBER Working Paper No. 9310. The National Bureau of

Economic Research. Retrieved from NBER Working Paper No. 9310:

http://www.nber.org/papers/w9310

31

Bohman, H., Laftman, S. B., Pááren, A., & Jonsson, U. (2017). Parental separation in

childhood as a risk factor for depression in adulthood: a community-based study

of adolescents screened for depression and followed up after 15 years. BMC

Psychiatry, 17:117

Bulduc, J. C., Caron, S. L., & Logue, M. E. (2007). The effects of parental divorce on

college students. Journal of Divorce and Remarriage, 46(3): 83-104.

Brown, M. G., Wohn, D. Y., & Ellison, N. (2016). Without a map: College access and

the online practices of youth from low-income communities. Computers &

Education, 92-93: 104-116.

Carlson, M., & Corcoran, M. (2001). Family structure and children’s behavioral and

cognitive outcomes. Journal of Marriage and Family, 63: 779-792.

Carnevale, A. P. & Rose, S. J. (2004). Left behind: unequal opportunity in higher

education, reality check series. The Century Foundation

Carnevale, A.P., Cheah, B., & Hanson, A.R. (2015). The Economic Value of College

Majors. Center on Education and the Workforce, Georgetown University.

Cavanagh, S. E., Schiller, K. S., & Riegle-Crumb, C. (2006). Marital transitions,

parenting, and schooling: Exploring the link between family-structure history and

adolescents’ academic status. Sociology of Education, 79: 329-354.

Center on the Developing Child at Harvard University. (2011). Building the Brain’s “Air-

Traffic Control” System: How Early Experiences Shape the Development of

Executive Function: Working Paper No. 11. Retrieved from

32

www.developingchild.hardvar.edu

Cherlin, A. J., Chase-Lansdale, P. L., & McRae, C. (1998). Effects of parental divorce on

mental health throughout the life course. American Sociological Review, 63(2):

239-249.

Cherlin, A. J. (2010). Demographic Trends in the United States: A Review of Research in

the 2000s. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(3): 403-419.

Conley, D. (2001). Capital for College: Parental Assets and Postsecondary Schooling.

Sociology of Education, 74: 59-72.

Copen, C. E., Daniels, K., Vespa, J., & Mosher, W. D. (2012). First marriages in the

United States: Data from the 2006-2010 National Survey of Family Growth.

Hyattsvill, MD: National Center for Health Statistics.

Devor, C.S., Stewart, S.D, & Dorius, C. (2018). Parental Divorce, Social Capital, and

Postbaccalaurate Educational Attainment Among Young Adults. Journal of

Family Issues 39(10): 2806-2835.

Ermisch, J., & Francesconi, M. (2001). Family Matters: Impacts of family background on

educational attainments. Economica, 68(270): 137-156.

FinAid. (2019). Divorce and Financial Aid. Retrieved from Financial Aid FAQ:

http://www.finaid.org/questions/divorce.phtml

Fingerman, K. L., Cheng, Y. P., Wesselmann, E. D., Zarit, S., Furstenberg, F., and

Birditt, K. S. (2012). Helicopter Parents and Landing Pad Kids: Intense Parental

Support of Grown Children. Journal of Marriage, 74(4): 880-896.

33

Foster, H., Hagan, J., & Brooks-Gunn, J. (2008). Growing up Fast: Stress Exposure and

Subjective "Weathering" in Emerging Adulthood. Journal of Health and Social

Behavior, 49(2): 162-177.

Fox, G. L. & Kelly, R. F. (1995). Determinants of child custody arrangements at divorce.

Journal of Marriage and the Family, 693—708.

Franklin University. (2019). Key Differences Between Undergraduate and Graduate

School. Retrieved from https://www.franklin.edu/blog/key-differences-

undergraduate-graduate-school

Frisco, M. L., Muller, C., & Frank, K. (2007). Parent’s union dissolution and adolescents’

school performance: comparing methodological approaches. Journal of Marriage

and Family, 69: 721-741.

Fröjd, S. A., Nissinen, E.S., Pelkonen, M.U., Marttunen, M.J., Koivisto, A.M., &

Kaltiala-Keino, R. (2008). Depression and school performance in middle

adolescent boys and girls. Journal of Adolescence, 31(4): 485-498.

Gennetian, L. (2005). One or two parents? Half or step siblings? The effect of family

composition on young children’s achievement. Journal of Population Economics,

18(3): 415-436.

Ginther, D., & Pollack, R. (2004). Family structure and children’s educational outcomes:

Blended families, stylized facts, and descriptive regressions. Demography, 41:

671-696.

Goosby, B. J. (2013). Early Life Course Pathways of Adult Depression and Chronic Pain.

34

Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 54(1): 75-91.

Gruber, J. (2004). Is Making Divorce Easier Bad for Children? The Long-Run

Implications of Unilateral Divorce. Journal of Labor Economics, 22(4): 830.

Hardesty, J. L. & Chung, G. H. (2006). Intimate partner violence, parental divorce, and

child custody: Directions for intervention and future research. Family Relations,

55(2): 200-2010.

Hayward, M. D., & Gorman, B. K. (2004, February). The Long Arm of Childhood: The

Influence of Early-Life Social Conditions on Men's Mortality. Demography,

41(1): 87-107.

Heard, H. E. (2007). Fathers, Mothers, and Family Structure: Family Trajectories, Parent

Gender, and Adolescent Schooling. Journal of Marriage and Family, 69: 435-

450.

Humensky, J., Kuwabara, S. A., Fogel, J., Wells, C., Goodwin, B., & Van Voorhees, B.

W. (2010). Adolescents with depressive symptoms and their challenges with

learning in school. Journal of School Nursing, 26(5): 377-392.

Ibrahim, A. K., Kelly, S. J., Adams, C.E., & Glazebrook, C. (2013). A systematic review

of studies of depression prevalence in university students. Journal of Psychiatric

Research, 47(3): 391-400.

Kessler, R. C. (2012). The costs of depression. Psychiatry Clinics of North America,

35(1): 1-14.

Lansford, J. E. (2009). Parental divorce and children’s adjustment. Perspective on

35

Psychological Science, 4(2): 140-152

Liu, S. (2007). The Effect Parental Divorce and its Timing on Child Educational

Attainment: A Dynamic Approach. University of Miami, Working Paper.

Marriage and Divorce. (2019). American Psychological Association. Retrieved from

https://www.apa.org/topics/divorce/.

Mehana, M., & Reynolds, A. J. (2004). School mobility and achievement: A meta-

analysis. Children and Youth Services Review, 26(1): 93-119.

Melby, J. N., Fang, S.-A., Wickrama, K., Conger, R. D., & Conger, K. J. (2008).

Adolescent family experiences and educational attainment during early adulthood.

Developmental Psychology, 44(6): 1519-1536.

Miller, G. E., Chen, E., & Parker, K. J. (2011). Psychological stress in childhood and

susceptibility to the chronic diseases of aging: moving toward a model of

behavioral and biological mechanisms. American Psychological Association,

137(6): 959-97.

Mintz, S. (2015). The prime of life: A history of modern adulthood. Cambridge, MA:

Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Mullen, A. L., Goyette, K. A., & Soares, J. A. (2003). Who goes to graduate school?

Social and academic correlates of educational continuation after college.

Sociology of Education, 76(2): 143-169.

National Longitudinal Surveys. (2018). The NLSY97 sample: An introduction. Retrieved

from https://www.nlsinfo.org/content/cohorts/nlsy97/intro-to-the-sample/nlsy97-

36

sample-introduction-0

Pearlin, L. I., Schieman, S., Fazio, E. M., & Meersman, S. C. (2005). Stress, Health, and

the Life Course: Some Conceptual Perspectives. Journal of Health and Social

Behavior, 46(2): 205-219.

Perna, L. W. (2000). Differences in the decision to enroll in college among African

Americans, Hispanics, and Whites. Journal of Higher Education, 71: 117-141.

Perna, L. W. (2004). Understanding the decision to enroll in graduate school: sex and

racial/ethnic group differences. The Journal of Higher Education, 75(5): 487-527.

Perna, L. W., & Titus, M. A. (2005). The relationship between parental involvement as

social capital and college enrollment: An examination of racial/ethnic group

differences. The Journal of Higher Education, 76(5): 485-518.

Radloff, L. S. (1977). The CES-D Scale: A Self-Report Depression Scale for Research in

the General Population. Applied Psychological Measurement, 1(3): 385-401.

Ross, C. E., and Mirowsky, J. (1999). Refining the association between education and

health: The effects of quantity, credential, and selectivity. Demography, 36(4):

445-460.

Schafer, M. H., Ferraro, K. F., & Mustillo, S. A. (2011). Children of Misfortune: Early

Adversity and Cumulative Inequality in Perceived Life Trajectories. American

Journal of Sociology, 116(4): 1053-1091.

Schilling, E.A, Aseltine, R.H., and Gore, S. (2008). The Impact of Cumulative Childhood

Adversity on Young Adult Mental Health: Measures, Models, and Interpretations.

37

Social Science and Medicine, 66(5): 1140-1151.

Shavit, Y. & Muller, W. (1998). From School to Work. A Comparative Study of

Educational Qualifications and Occupational Destinations. Oxford University

Press, 2001.

St. John, E. P., & Wooden, O. S. (2005). Humanities Pathways: A Framework for

Assessing Post-Baccalaureate Opportunities for Humanities Graduates. In M.

Richardson (Ed.), Tracking Changes in the Humanities (pp. 81-112). Cambridge,

MA: American Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Strohschein, L. (2005). Parental divorce and child mental health trajectories. Journal of

Marriage and Family, 67: 1042-1077.

Sun, Y., & Li, Y. (2001). Marital Disruption, Parental Investment, and children’s

academic achievement: a prospective analysis. Journal of Family Issues: 22: 27-

62.

Sun, Y., & Li, Y. (2011). Effects of family structure type and stability on children’s

academic performance trajectories. Journal of Marriage and Family, 73: 541-556.

Sutherland, A. (2014). How Parental Conflict Hurts Kids. Institute for Family Studies.

Retrieved from https://ifstudies.org/blog/how-parental-conflict-hurts-kids/

Thomas, S. L., & Zhang, L. (2005). Post-baccalaureate wage growth within 4 years of

graduation: The effects of college quality and college major. Research in Higher

Education, 46(4): 437-459.

38

Umberson, D., Crosnoe, R., & Reczek, C. (2010). Social Relationships and Health

Behavior Across the Life Course. Annu. Rev. Sociol. Annual Review of

Sociology, 36(1): 139-157.

Uphold-Carrier, H. & Utz, R. (2012). Parental Divorce Among Young and Adult

Children: A Long-Term Quantitative Analysis of Mental Health and Family

Solidarity. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 53(4): 247-266.

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2014). Income, Assets, & Program Participation: An

Introduction. Retrieved from National Longitudinal Survey of Youth 1997:

http://www.nlsinfo.org/content/cohorts/nlsy97/topical-guide/income/income-

assets-program-participation-introducation

U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics (2016). Projections of Occupational Employment, 2016-

26. Retrieved from

https://www.bls.gov/careeroutlook/2017/article/mobile/occupational-projections-

charts.htm

U.S. Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. (2006). Librarians. Occupational

outlook handbook, 2006-07. Retrieved from

https://www.bls.gov/nls/y97summary.htm

Vandewater, E. & Lansford, J. (1998). Influences of family structure and parental conflict

on children’s well-being. Journal of Family Relations, 47: 323-330.

39

Veit, C. T. & Ware, J. E. (1983). The Structure of Psychological Distress and Well-Being

in General Populations. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 51: 730-

742.

Wallerstein, J. S., & Lewis, J. M. (2004). The Unexpected Legacy of Divorce: Report of

a 25-Year Study. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 21(3): 353-370.

Wickrama, K. A., Conger, R. D., Lorenz, F. O., & Jung, T. (2008). Family Antecedents

and Consequences of Trajectories of Depressive Symptoms from Adolescence to

Young Adulthood: A Life Course Investigation. Journal of Health and Social

Behavior, 49(4): 468-483.

Wickrama, K., Kwon, J. A., Oshri, A., & Lee, T. K. (2014). Early Socioeconomic

Adversity and Young Adult Physical Illness: The Role of Body Mass Index and

Depressive Symptoms. Journal of Adolescent Health, 55(4): 556-563.